Photos

Right-click [Mac Control-click] to open full-size image:

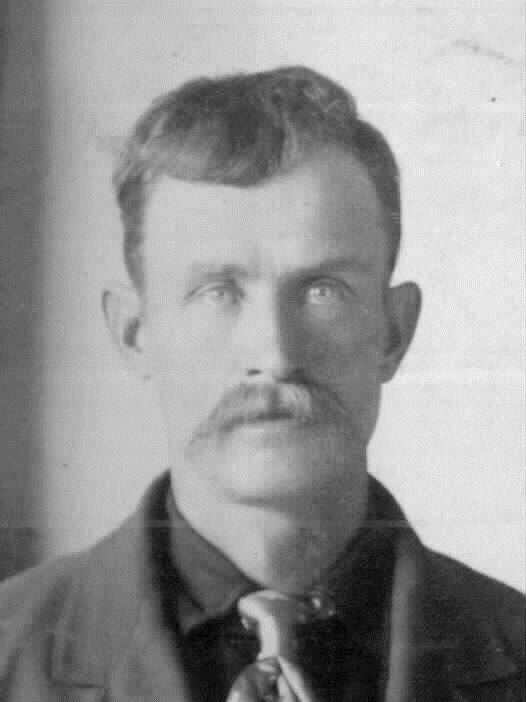

Charley Walton

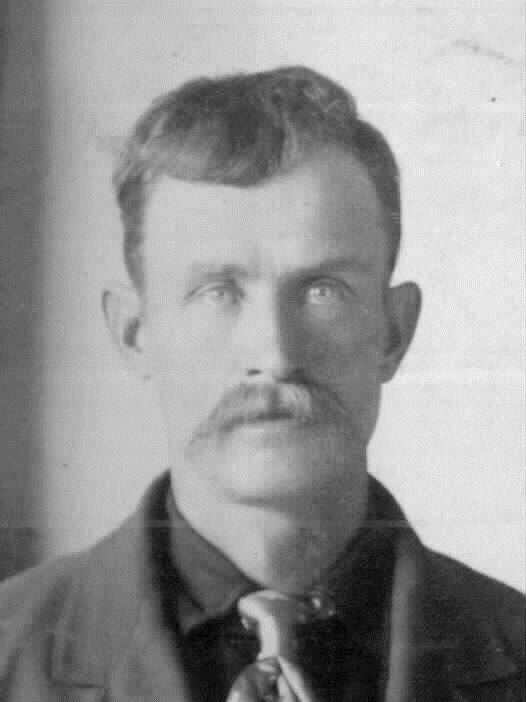

Emma Louise Hyde

Source

FamilySearch:Charles E Walton Jr

-- contributed by Joyce Ann Hunt

Born: 28 January 1868 in Bountiful, Davis, Utah

Parents: Charles Eugene Walton, Sr. and Jane McKechnie

Married: Charles Eugene Walton, 16 February 1867 at Salt Lake City, Salt Lake County, Utah

Died: 24 July 1891 in Monticello, San Juan County, Utah

CHARLES EUGENE WALTON, JR. -- A LIFE SKETCH

Charles Eugene Walton Jr., son of Charles Eugene and Jane (McKetchnie) Walton, was born 28

January 1868 in Bountiful, Davis County, Utah. At the age of about four years, he moved

with his parents to Woodruff, Rich County, Utah, where the parents were engaged in farming

and stock raising. It became the duty of Charles Jr. to heard cattle.

He started to school at the age of seven years in a typical frontier school house where

one teacher held sway over the temporary destinies of all grades and ages. His first

teacher was Van Putnam, grandson of Ruth Walton and Israel Putnam. Each session of the

school faithfully commenced with prayer and song, and a standing salute to the flag.

The young Charles was about ten years of age the summer the family moved to Hillard Mountains

of Wyoming, where his father was engaged in cutting cordwood. The boy was sent out horseback

each day to deliver milk to the woodchoppers. One day as he was sent on his regular milk

delivering routine his serenity was considerably upset by the demands of his sister, Maggie

(Magnolia) wanting to accompany him. He didn’t want any old girl along! But the ancestral

Scottish and New England tenacity of purpose was as strong in her as it in him. — She went

along, perched up behind him as the pony jogged along the woodcutters trail with its odd

burden of children and milk cans jangling an accompaniment. Leaving home about 7 A.M. they

were expected home again by 10 A.M. That morning while the children were gone, a forest

fire broke out in the vicinity and crossed the trail by which they were to return, which

made their chances for return very dangerous. The children were frightened on being

confronted with this peril, but thinking only of the home and the mother and baby alone on

the other side of the fire, there seemed to the boy nothing to do but ride through it.

Imagine the consternation of the woodcutters behind them and the mother ahead, each cut

off from making a rescue of the two-trapped children. With the confidence of youth and

exasperation of necessity the boy held tightly to the girl behind him with one hand and

held the bridle reins with the other, and stubbornly urged his horse at a run through the

falling, crackling, smoking timber, and miraculously came through in time to help his

mother remove from the little log dwelling every stick of furniture including a heavy cook

stove.

In October 1879, his father received a call from the Church to take his family and

possessions and join the company of people who were called to go into the San Juan County

and help to establish the San Juan Mission. Indians had been making raids on white

settlements over a wide radius of the country, stealing horses and generally making trouble.

One of the main purposes in calling these settlers was to establish peace and friendship

with the Indians. Apostle Erastus Snow and Silas Smith were the men in charge of this mission.

Silas Smith was appointed leader of this mission, but having also been elected to the

Legislature, he left Jens Neilson and Platt Lyman in charge.

Charles Jr. was eleven years of age at this time. His duties for the journey were as a

herd boy. He was to make the long ride horseback and drive the stock. The outfit

consisted of a yoke of wild steers, a yoke of wild bulls, five horses, a colt, and eleven

head of cattle. At Salt Lake City they added a cook stove and other supplies for the

long journey ahead. Being a boy he found much interest and none of the worries of

responsibilities in this exodus.

Traveling by this slow method the family were about six weeks going from Woodruff to what

is called “Forty-mile Spring” out on the Escalante desert, where the main company of more

than eighty wagons were camped. While camping at this place, a scouting party was sent

out to find a feasible route by which the wagons could be taken to their destination.

When these scouts returned, it was with the report that “a bird could not fly over the

route, let alone teams and wagons getting through.” A council was held in the camp and

brother Jens Nielson, later to become their Bishop, made a promise to them that if they

would not give up but go on, that a road could be built and that it would be built and a

crop would be raised the next season. It was now mid-winter in 1879. The company moved

slowly onward till it reached what they called the Hole-in-the-Rock where they again made

camp and began the arduous task of making a road across the Colorado River. The company

camped at this spot for six weeks.

The Hole-in-the-Rock was a formation of cliffs with a narrow crack or opening or space too

narrow to take a horse through. This cliff dropped forty feet to a slanting shelf like a

place with a steep descent from there to the canyon below. To make a road here it was

necessary to blast the rock with black powder to widen the opening and to fill in the

crevices to make a road bed down to the shelf below.

Young Charles had his place in the road building. He said he was the water carrier, also,

being but eleven years of age, he was slight of build and light weight. Tying a rope about

his waist, they lowered him down over the cliffs to place the powder in the crevices and

prepare it for the explosion. About six weeks were spent at this road building before the

wagons could be taken through. The road was finished during the end of December 1879.

When the time came to move, it was necessary to tie ropes to each wagon’s rear end then

while six or seven men pulled back on the wagons with all their strength to keep the wagons

from gaining too much speed down the steep incline, which would have been disastrous to

both wagons and oxen, they moved forward. When the last wagon was over the top and down

to the river’s edge, they had to be ferried across the river. The horses and cattle were

driven into the 300 hundred foot wide river and forced to swim across while the wagons

and people were taken across on a raft they had built for that purpose. It was about

sundown around January 28, 1880 when the Walton family and possessions crossed the river.

Then they loaned a yoke of oxen to Jim Hunter to bring his load across the river. Mr.

Hunter hitched the oxen to his wagon and waited his turn to cross. He was advised to

unfasten the team until ready to start but he felt it unnecessary to do so. However, upon

insistence from the owner he did so and just in time, for the restless oxen walked into the

river and swam across, dragging the chain with them, but fortunately, leaving the loaded

wagon still on the raft. Charles turned twelve years old the day his family crossed

the river.

About 15 miles from the Hole-in-the-Rock, across the river, they established what they

called “Cheese Camp”, and thereby came a tale. Silas Smith, who was supposed to have this

company in charge, was now in the State legislature. Through his efforts there, an

appropriation was made for this company of colonists to purchase tools, powder, and supplies.

Among the provisions and supplies appropriated, was a wagonload of cheese. The cheese was

brought to camp and cut up. That night by the light of the campfire the cheese was

auctioned off to the road workers for road script time he had worked. In auctioning the

cheese, it was paid for by this script. Thus, the camp was called Cheese Camp.

They traveled across a flat sagebrush area called Grey Mesa for a little while. When the

mesa ended they came across what the early pioneers called Slick Rocks. It was massive

sandstone cliffs reaching about a thousand feet, another formidable obstacle. They camped

at Slick Rock, which previously the scouting party had found to be the most formidable

barrier. It was the barrier that had turned some other scouting parties back with the

message that they could not get through. It was at this place where one party had about

given up in despair, when a mountain sheep, eluding capture, unwittingly led one of the

men down the trail by which a road could be built. The weary worn company traveled and

built roads until finally on April 6, 1880, after having built another road up the side of

a cliff they arrived at the site of the present Bluff City, and there, their wagons

literally fell apart and the weary pioneers of San Juan decided to stay.

They reached this new home on the 6th of April 1880. This six weeks journey had taken

six months to complete. It had been one of the most severe winters in many years. On

the trek they averaged only 1.7 miles per day, the slowest rate of any American wagon

train that had brought settlers west. These pioneers never gave up, they had done what

no one else had done.

They built a fort in which all the families lived for about two years. They dug ditches

and got irrigation water onto the land, then proceeded to plant the crops Brother Nielson

had predicted would be raised that season. The duties of a boy in a pioneer settlement

were many. Charles became the herd boy for all the settlement. He established a friendship

among the Indians, which lasted, through out all his life. He swam with them in the San

Juan River, and played with them in their camps. He often visited with them in their

camps during their festivities such as their “Corn Dances” and their “Rain Dances.” As

he grew older the stores hired him to cross the river in a boat and row the Navajo’s back

with their goat skins, wool etc., to trade in Bluff. The Piute’s were also friendly with

him. They would come to his home when hungry and were fed, which hospitality was in turn

offered to him in their wickiups.

The first meetings in Bluff were held under a giant cottonwood tree, which in time became

known as the “Swing Tree”, because the community used it as a recreational center. The

first meeting house which had the dual purpose of serving as a church and a school house,

as well as the indoors social center, was built of cottonwood logs with a dirt floor and

a stage for convenience in the seating of the Bishopric on Sundays, or a stage play on other

occasions. The floor and the benches had the distinction of being made of crudely fashioned

wood boards. To make the boards, a large hole was dug in the ground, and with a man in the

hole and a man on top, each holding one end of a rip saw and a log rolled over the hole,

then by operating the saw up and down, the log was split into a sort of lumber.

Provisions and supplies were obtained by traveling and freighting from Colorado. At first,

from Alamosa in the San Luis Valley, but later from Durango which was a newly built mining

town. Sugar Cane was grown in Bluff and the pioneers made their own molasses. One day a

wagon load of supplies arrived, and this turned out to be shoes and clothing supplies,

which were badly needed by the now improvised pioneers. So anxious was Charles Jr. to

have a new pair of boots, that he got a pair that were a size too small. He crowded his

feet into them but it was a crippling job to walk.

In the summer of 1881 a town site was surveyed and each family commenced building on its

own lot. Then a county was established and named San Juan. Silas S. Smith was appointed

Judge and Charles Eugene Walton Sr. was appointed Clerk of the Court. It was about this

time San Juan was changed from the Middion [Midian] to the San Juan Stake. This stake

included parts of Colorado and New Mexico as well as Moab, Grand Country, Utah.

Disaster came upon the colony at Bluff bringing discouragement to its people. The San Juan

River overflowed its banks, washed out the ditches, and destroyed the crops and took away

much of their land and property. The pioneers about decided to pack up what belongings

they had left and seek again a new home. Elder Joseph F. smith, who later became the

President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was sent to investigate and

to release the settlers from the mission, if he saw fit. But after holding Conference and

making this a matter of prayer, he advised the people to remain. Never-the-less, those

wishing to move away would be released with the blessings of the Church. Charles Walton,

Sr. and family stayed at Bluff.

Sometime during the winter of 1886 and 87 there was a plan established for the settling of

a mission in the higher country where the mountain streams could be utilized. Accordingly

an irrigation company was organized and in the spring of 1887, Charles Jr. now eighteen,

with several other men. Charley, his father, Charles Sr., F.I. Jones, Nephi Bailey, Mons

Peterson, and Edward Hyde, received the call to establish a settlement in the Blue

Mountain country. They went to Verdure where they were kept busy making roads, surveying

town sites, and digging ditches for the future settlements. Charles Walton Sr., arrived

at the present site of Monticello in the fall of that year with a load of lumber, which

he unloaded on the ground which became the home of Charles E. Walton Jr. They were kept

busy making irrigation ditches and surveying a town site. His sister Leona and another

young lady by the name of Emma Hott cooked for the men over a campfire in a three-sided

shelter of “Shanty” made from lumber that Charles Jr. hauled in from Delores, Colorado.

For his work that year Charles received one ton of hay, four bushels of oats, four sacks

of potatoes, and six bushels of wheat. The next summer with the coming of a number of

families to live in the new settlement, they hauled logs from the mountains and built a

log house for each family. The Walton family had the only house with lumber roof, the

others being of sod.

One of the first problems of the new community was the choosing of an appropriate name.

The older men of the new town met for this purpose and President Hammond suggested

“Antioch” as a good name. They decided to meet another day to make it official, but the

younger men and girls were not happy about the name. They shrewdly met together and upon

the suggestion of Charles, who had just read the Life of Thomas Jefferson and liked the

name “Monticello” better for a name. They launched a clever “whispering campaign’ and

much clever propaganda in favor of the name “Monticello” instead of “Antioch.” So subtly

was it done that when the older and wiser men met to make the name official, they seemed

to have forgotten their original intentions, and upon the motion of Charles Eugene Walton

Sr., the name of Monticello was presented and it was voted unanimously.

The first year in Monticello every family was instructed to plant five acres of grain.

Having no machinery the first crop was cut by hand with a scythe or sickle. Charles Jr.

cut all the grain, with the men to stock it. The grain was then flailed out by hand.

John E. Rogerson and Charles E. Walton, Jr. was expert with the scythe and cradle and were

in great demand until the advent of the reaper and mower. In 1888 Charles E. Walton

purchased a horsepower thresher and went over the county doing custom work as far away as

Colorado and New Mexico.

When the government with a post office and weekly mail service dignified Monticello,

Charles Jr. was appointed its first Post Master, the commission being granted by President

Benjamin Harrison. This position he held, with the exception of eight years, until

October 1934. When he was 25 years of age, his father was called on a mission to the

Southern States, and Charles Jr. was called to be second counselor in Bishopric to fill

the vacancy left by his father’s mission.

A brass band was formed and a mandolin and guitar club. Soon most of the men were “blowing

a horn” or beating a drum while the young folks strummed the strings. The names mentioned

in the band were: Charles E Walton, Jr., Fredrick I Jones, Daniel H Dalton, Frank Hyde,

Nephi Bailey and George A Adams. A close second to music in the pioneer culture was the

presentation of amateur plays. Charles E. Walton Jr. and Edward and Emma Hyde were just

some of the local actors.

Charles Jr. married Emma Louise Hyde on January 28, 1896. Emma Louise was set apart by

Bishop F.I. Jones to care for the sick and take care of the dead in 1908. She held this

position for 36 years. Since there were no undertakers or doctors in this new community,

everything pertaining to the dead was cared for by her and her two assistants. Her work

included covering the caskets and making burial cloths and dressing the dead, as well as

caring for the sick. She served as Relief Society President and was on the Stake Relief

Society Board.

Charles Eugene Walton Jr. died on May 9, 1945 in Monticello at the age of 79. The following

was the obituary that was published in the San Juan Record May 15, 1945:

The passing of Charles E. Walton last Friday evening after a short illness means that

Monticello has lost one of its finest men of pioneer stock. Although in failing health

for the past few months, Mr. Walton has been seen about town almost daily and will be

sadly missed by family and friends.

At his funeral, Mr Dan Perkins spoke of the faithful service rendered during many years

of association with the folks of Bluff, Vendure, and Monticello. Mr. Walton was

instrumental in the establishment of each action, having come with his parents, when a

lad of twelve, with the first Mormon settlers through the “Hole in the Rock”. He also

paid tribute to Mrs. Walton telling of her continued service throughout the years.

Bishop Oscar McKonkie (McConkie) of Moab, who prefaced his talk by telling of his

humbleness in the presence of pioneers like Mr. Walton. He brought out the point that

all thru his life Mr. Walton realized that he came to earth for a definite purpose and

that all trials and testings were but a part of the plan of living which must be met and

overcome.

Bishop K. S. Summers paid tribute to Mr. Walton for the faith instilled that brought

understanding and knowledge of the rightness of all things.

Written by Pearl L Walton, Monticello, Utah

Right-click [Mac Control-click] to open full-size image:

Charley Walton

Emma Louise Hyde