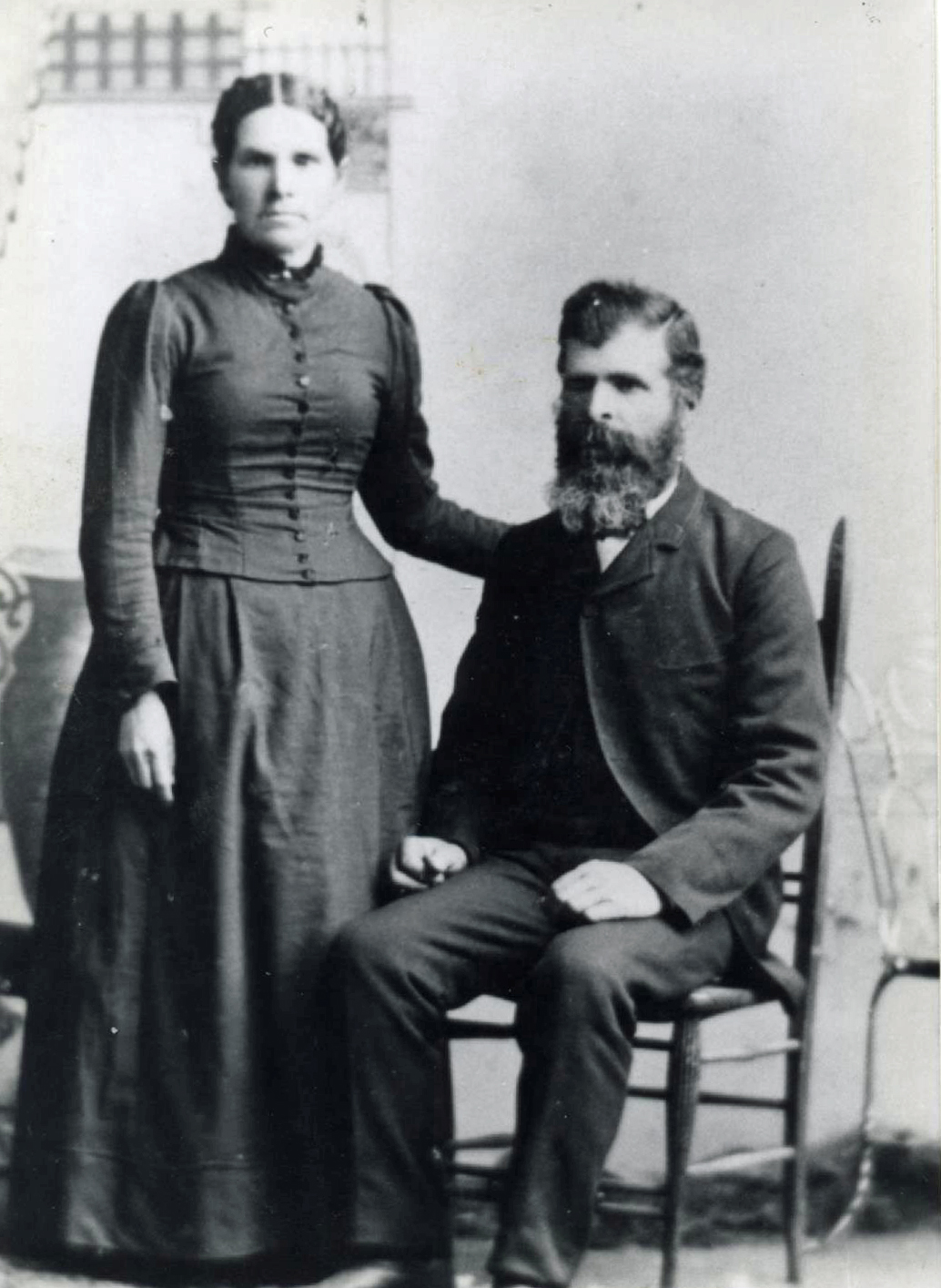

History of Samuel and Ann Taylor Rowley

Samuel Rowley

Born: 29 October 1842 at Mars Hill, Suckley, Worcestershire, England

Parents: William Rowley and Ann Jewell

Married: Ann Taylor, 23 April 1865 at Parowan, Iron, Utah, United States

Died: 8 January 1928 at Huntington, Emery, Utah, United States

Ann Taylor

Born: 24 April 1846 at Arnold, Nottinghamshire, England

Parents: George Taylor and Mary Franks Smith

Died: 14 Jan 1901 at Huntington, Emery, Utah, United States

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SAMUEL ROWLEY

I, Samuel Rowley, was born the 29th day of October, 1842, at Mars Hill in the Parish

of Suckley, Worcester,

England. My father, William Rowley, was born 21st of

June 1785, at Cradley, Herefordshire, England. He lived

all his life in southern England: Hereford, Worcester, and

Gloucester.

At the age of 22, he married Ann Jewell on the 2nd of

June, 1807. Seven children were born to them. Ann suffered

with poor health and died soon after her youngest child was

born, leaving William to care for them as best he could.

My mother, Ann Jewell, was living in the home as the

children's governess. She was the daughter of William Jewell

and Frances Green born on the 5th of December, 1807, in Leigh,

Worcestershire, England.

It was the law in England at that time that no female

could remain in the home where there was a single man.

William knew that he must find a mother for his children.

He knew Ann was a good woman and loved his children and he

had respect for her, for the love and respect she had shown

for the family, and the children wanted her to stay. He

felt he had found a good mother for his children. He married

my mother, 22 August 1836, and the children readily accepted

her as their new mother.

This was a great undertaking for Mother, as the oldest

of the children was nearly as old as she was, but through the

increasing of love and respect and trust they had for each

other a happy and contented home was enjoyed by all.

Their first child was born the 8th of May, 1837. They

named her Louisa. She was born in Leigh, Worcester.

My father was considered to be a well-to-do farmer and

horticulturist. They had a comfortable home, surrounded by

lawns and orchards. Father was a good provider. He raised a

good garden of hop vines. selling hops, fruits, and

vegetables at the market place. We were a happy family.

My parents were very devout in their beliefs. They had

joined a sect known as the United Brethren, along with many

other people in that section of England. They had broken off

from the Wesleyan or Primitive Methodist faith with a Mr.

Thomas Kingston as Superintendent, and were becoming quite

active at that time. (This Mr. Kingston and most of his

followers later joined the Mormon Church.)

Mother and Father were always searching for some light

and truth. They spent much time reading the Bible, and in

prayer. They were prospering, and their family was also

increasing. On the 14th of December, 1838, my sister

Elizabeth was born.

In 1840, Elder Wilford Woodruff came into England. He

was one of the Apostles of the Mormon Church, known as the

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He and his

companion were speaking at the house of John Benbow,

a wealthy farmer cultivating 300 acres of land. Occupying

a large mansion with no family, the Benbows gladly offered

lodging to the missionaries. Mr. Benbow and his wife were

also part of the 600 United Brethren which also included

my parents. He offered space in his home for the meeting.

My parents attended and were converted, which resulted in

the baptism of my mother. She was baptized and confirmed

on the 6th of May, 1840. Father was baptized and confirmed

on the 24th of May, 1840, at Nightingale Bower near Birenwood

and Tapperdv. (These dates were recorded in the

Baptismal Journal of Wilford Woodruff himself.)

After the baptism, Elder Woodruff and his companion

preached at Dunn's Close, walked four miles from Benbow Farm

Pond, and spent the night at my parents' home. My father was

ordained a Deacon by Wilford Woodruff on his second mission

in 1841.

One night, so I've been told by my mother and

older sisters, a mob of men came to my parents' home and

demanded to have the Elders. Father, standing in the door,

told the men that they had gone to bed and were guests in

his home and were not to be disturbed. This did not satisfy

the angry mob and they said they were going to get them.

Father said it would be over his dead body. They grabbed

Father and dragged him away from the house. He called to my

Mother to lock the doors and the windows, which she did.

They beat Father severely and thought he was dead. They then

went to the house and tried to get in, but found everything

locked up. The mob was afraid to break into the house, so

they mounted their horses and rode away. When Mother

couldn't hear the hoof beats of the horses, she felt safe to

go out to Father. She found him still conscious, but in

bad condition. She helped him to the house and doctored

him through the night. When morning came and the Elders

arose, they found him badly bruised and in bad condition,

and they advised my parents to sellout and prepare to go

to America. This advice they accepted and as my father

improved in health, they began working and saving to get the

finances to leave. It was hard for my father to part with

his life's work.

More children came to bless my parents' home. My

brother, John, just older than I, was born July 14, 1840.

One time when John was a little boy and Brother Woodruff came

to our home to visit, he patted John on his head and said

that he had baptized John before he was born. That was

because he was born in July after our Mother was baptized in

May.

I was born October 29, 1842, the same year the General

Relief Society was organized in Nauvoo. Richard came next in

line, he being born on the 10th of February, 1844. On the

11th of May, 1846, another brother came, named Thomas.

Another little sister, Jane, was the last child, born on July

17, 1848.

The next few years, many hardships got in the way.

Drought caused the crops to fail for two years in succession.

My parents were forced to sell their home and farm at Public

Auction. This was a great blow to them. Then the climax

came when Father had an accident while traveling to the

market place with some crops to sell. The horse became

frightened and ran, throwing Father from the wagon and running over his body, injuring his leg and hip. This injury,

along with much worry over financial heartache, was more than

Father could stand, and his body could take no more. His

death, on the 14th of February, 1849, brought relief to his

tired body, but oh, the heartache and troubles it brought for

Mother. She was left alone now with seven children of her

own to guide and support, along with sadness and worry. This

took much faith and courage on her part. She was of strong

character. Faith and prayer buoyed her up as she set forth

to accomplish to the best of her ability the task of getting

her family to America. She knew that Father would want her

to. She had seven small children of her own and some of the

younger children of her husband by his former marriage. The

oldest step-child at home was frail, unable to take on heavy

responsibilities.

I was only seven years old at the time my father left

us, and John was only two years older. Mother found a job

for us three miles from where we lived. Mother would get

John, Richard, and I up early, give us a light breakfast, if

there was some to have, and take us by the hand and go with

us to our job at a brickyard, where we carried bricks to

stack and tromped mud with our bare feet. On our route, we

had to cross a stream of water with only a narrow bridge. My

mother made sure we were safely across the bridge and that we

were wide awake. She would then walk back to her work at her

brother, Thomas Jewell's, who was a tailor by profession.

She was very efficient with her needle, making men's

clothing. She also did sewing, making fine clothes and

draperies for her sister who had married a wealthy man.

Her brother told her that if she would leave the Mormon

Church and get back where she was before, she would never be

without work. He also told her that if she died as a Mormon,

she would be buried behind the church instead of at the

front, but her testimony of the truth of her religion gave

her strength to carry on and save what she could with the

girls working, too. Elizabeth worked with her at the shop

making smock frocks, which were in demand. Louisa worked

diligently at her job, also, and they were slowly able to

save a little money.

One day the word came from President Brigham Young telling

the Saints desiring to go to the land of America of an

emigration fund from the Church headquarters in America.

The fund would pay the way to get to America and also buy

handcarts and supplies. However, it also included the

invitation to walk 1300 miles to the Rocky Mountains. Mother

felt that the way had been opened up for the family to leave

England, our homeland, and be with the Saints and to have a

new start. Also, by the time we could leave, John would be

old enough for the army. (At this time a war between England

and Russia was in progress.) Mother was very anxious to get

him away from there. So everyone worked as fast as they

could to get what was needed to take with us. Mother tried

to persuade Eliza to remain with her own brothers and sisters

because of her weak condition. She knew that the journey

would be especially hard on her, but Eliza had such a great

feeling for my mother that she felt she couldn't remain

behind, so Mother, showing her love and feeling for Eliza,

consented to take her along.

At last the day came when we could embark. On the 4th

day of May, 1856, we sailed on the ship Charles Thorton, a

sailing vessel. Our experience on the sea was exciting.

Several things took place that tested our faith. During

one storm we had wind that drove us back 500 miles. Another

time the ship was in a calm with no wind at all, and we sat

in one place. The Saints fasted and prayed and the wind came

and we traveled on. Another time the ship caught fire. Our

Captain asked us to fast and pray for help and the Lord sent

the rain to put out the fire. Captain Collins recognized

that the blessings the Saints had received had saved the

ship, and the Saints were given privileges that others didn't

get. He was very good to the Saints but a cruel man to his

crew.

The ship arrived in New York on June 14th, 1856 and we

were received by Elder John Taylor. After landing at Castle

Gardens, we sailed up the Hudson River to the terminal of the

Rock Island Railroad. We traveled by railroad and boat to

Iowa City, then to Council Bluffs. Here we were to prepare

for one of the worst journeys that has ever been recorded.

The Saints were lighthearted and worked with zeal preparing

their handcarts. They were being put together with

green timber as timber was scarce then because so many Saints

were anxious to get on the road. The wheels were wrapped

with rawhide strips to hold them together. While they were

being built we were busy getting our supplies together and

getting cattle bought and broken. We waited several weeks,

going to prayer every morning and night.

We left Iowa campground with handcarts bound for Salt

Lake Valley, 1300 miles in the distance. We left under the

leadership of James C. Willie and Milan Atwood. Before we

left, Elder Levi Savage, who was returning from a mission,

spoke of the intense suffering the Saints would have to

endure if they left--and he cried like a child with the

thought. At this meeting he spoke of the lateness of our

start, and predicted the cold and suffering that would be

encountered before we would arrive at the Valley. Mr.

Willie rebuked him for this speech. He was afraid it would

dishearten the people and he told them that if the Saints

would be faithful and do as he told them, winter would be

turned into summer. But subsequent events proved that Elder

Savage was correct. A few of the Saints preferred to wait.

The others, with buoyant spirits, started to draw their carts

from Council Bluffs.

It was on the 15th day of July, 1856, that the Willie

handcart company left. This company consisted of 500 souls,

120 handcarts, five wagons, 24 oxen and 45 beef cattle.

The first 100 miles went well, with the scenery being

beautiful and the game along the way being plentiful. The

spirit of joy reigned in this camp of Israel.

However, on the 5th day of September, the company cattle

were

off by a storm. Approaching in advance of a storm

a large herd of buffalo were on the stampede. They came by

our camp and about 30 head and our best yoke of oxen were

swept away with them. We hunted several days for them, but

had to give it up. With our oxen gone we had to put 100

pounds of flour on each cart and our rations were reduced at

the same time.

As we started out the weather was hot and our feet would

blister. The open sores were unbearable. Later they would

become calloused and crack open. The cattle had to be herded

at night so they wouldn't stray away and get picked up by the

Indians. This was very hard on the men and boys after a hard

day's pushing or pulling a handcart. They got very little

sleep or rest. When going up hills it was hard on them, then

going down hills it was hard to hold back.

One night at camp, it seemed we were going to go to bed

hungry. My dear mother brought out two very hard sea

biscuits that she had put away while on board ship. She said

they were kept for a rainy day. She put them in the skillet

and poured water over them and we knelt in prayer while she

asked the blessing over them. When the lid was removed, we

were very happy to see a full pan of food, enough for the

whole family. We again thanked the Lord for such a wonderful

blessing.

Due to the rush in making the carts, the wheels had been

wrapped with rawhide as they were made of green timber, and

now they were getting rickety and hard to push and pull. The

weather was getting very cold, rations were short, and work

was hard. Our dear sister Eliza could no longer endure these

hardships. In October, 1856, she went to rest and was buried

in a snow bank on the plains.

This was a hard blow on Mother, to leave her there know

ing that as the snow melted away, the wolves and other

animals would devour her body. It was also hard for

Mother to see her family trudging along with sore feet from

walking in all kinds of weather, with blistered feet in the

summer making them very tender for the winter.

Also somewhere along the way, Mother had a piece of

sagebrush get in her eye, which was very sore and became

worse in cold weather.

As winter approached, the suffering became almost impossible.

As we waded through streams of water, our

clothes would freeze almost to our limbs, making progress

very painful. Many people died by the wayside from the

extreme cold and scant food.

We had to cross the Sweetwater three times. The last

time we crossed, we had the last dust of flour dealt out to

us. Captain Willie and Brother Elder went in search of food.

(About this time, Cyrus Wheelock of the Dan Jones Party met

them with provisions. He could not restrain the tears when

he saw the condition the Saints were in. Many were unwise

and ate more than their shrunken stomachs could hold and died

from the effects of it.)

My oldest sister Louisa shared, as much as it was

possible for a girl, in all the cares and heartaches of the

Journey. One night, after helping to push the handcart all

day, she was taken sick with severe cramps. Mother and

Elizabeth sat by her side trying to relieve her discomfort

as best they could with what little they had to do with,

which was mostly encouragement. Next morning she was partially recovered,

but needed to be put in the sick wagon.

That provoked Captain Willie and he abused her shamefully.

He was very unkind to the Saints and when someone

suggested to have some of the Church cattle that he was

bringing for food killed to save the Saints from starving, he

replied that he would rather save the cattle than the people.

One night we had to make camp without water. Fifteen

people froze to death and had to be left by the wayside. My

brother John gave out before reaching camp and lay down on

the ground. When the captain saw him, he served him a

severe kick. As he groaned it indicated that he was alive,

so he had to be put in the sick wagon. My mother had to

melt snow to thaw our hair from the ground where we

slept. My youngest brother Thomas's hand was badly frozen

while holding onto the cart to keep up with the family.

When he got up by the campfire, it swelled up until it looked

like a fat toad. It was very painful and it stayed fat the

rest of his life. My mother had often said she'd be the

happiest woman on earth if she could enter the Salt Lake

Valley with all her children, and with the exception of one

she raised like her own, she was blessed to enter the Salt

Lake Valley with all her own.

Before we reached the Valley, Elder Franklin D.

Richards and a company of Saints who were passing our camp

saw our plight and rode with haste to Salt Lake and reported

it to President Young at the October Conference. As soon as

Conference came to a close, President Young addressed the

Saints and told them that there were a number of Saints on

the plains on their way to Zion with handcarts and that they

needed help. Twenty wagons and teams were needed by the next

day to go to their relief. It would be necessary to send two

experienced men with each wagon. He said that he would

furnish three teams and wagons loaded with provisions and

send good men, and Brother Heber C. Kimball would do the

same. If there were any brethren present who had suitable

outfits for such a journey they should make it known at once

so they would know what they could depend on.

When the rescue party reached Fort Bridger they became

alarmed as they had expected to meet the Willie Company at

this point. After some deliberation the decision was made to

send Joseph Young and Cyrus Wheelock ahead to urge the

company on if possible.

Soon the snow became so deep and the wind was blowing

from the north so cold that they had to camp-for the men and

animals were completely exhausted. It was here on October

20th that Captain Willie and Joseph Elder, riding on two

worn-out animals, brought the news to the relief parties

that unless immediate aid came, the Willie Company would

perish.

The men soon prepared to start out again, and after a

hard journey, they arrived at our camp. There they found

people who had not eaten for 48 hours. Immediately fires

were made and food was prepared. For some, the rescue party

was too late, for that night nine more deaths occurred. Part

of the rescuers stayed with the Willie Company, but some

pushed on to rescue others along the way. We had been forced

to discard some of our bedding back aways when the snow had

become 18 inches deep, making it impossible to push through,

and now we really needed it to keep warm. A rescue party

came to us under the direction of George D. Grant after we

had been in camp for two days, and they had a wagonload of

provisions.

We started on our way again after this rest. We crossed

the river again and marched all day through the snow in our

wet clothes. We soon received plenty of help from the Valley

and our scanty belongings were hauled in wagons. I thought I

could take our cart in alone, but I could soon see that I

couldn't take it any farther, so I reluctantly turned it out

of the road in among the cedars. From there I could ride

whenever we came to a downhill haul. We arrived in the

wonderful Valley of our new homeland on November 19, 1856.

Upon our arrival in the Valley in the mountains many

people had friends or relatives to greet them but the Rowley

family had no one. Still, my mother bowed her head and

thanked the Lord that she had been blessed to get to the

Promised Valley with all her own children alive, even though

not in the best of health.

Providence provided kind friends to supply our needs.

Mother found some good soul who removed the piece of

sagebrush which had caused so much pain and discomfort for

most of the journey from her eye. Brother John, who was

still disabled with frozen limbs, was cared for by a family

in the city. Elizabeth also lived in the city, praying to

find employment, which she did. Mother and three of her

children; myself, Thomas, and Jane, were sent to Nephi, Juab

County. where I remained until 1858.

My sister Elizabeth had married a native of Nephi by the

name of David Udall. I worked for him until our Bishop

learned that a man in Provo needed a boy my size, so I was

sent there to him. I was given a place for sleeping quarters

at the corral. After a few days I began to think that I was

better off with my family in Nephi, as I was not receiving

much kindness. I had had it, so one morning in January with

10 inches of snow on the ground and without dinner or lodging

I started for Nephi. While crossing Payson Bottoms I met a

man from Santaquin. After he asked me a few questions, he

became interested in me and told me when I got to Santaquin

to inquire for Web's place and they would take care of me.

The next day I rode to Nephi.

In the spring of 1858 a man from Iron Co., Andrew

Bastian by name, came to Nephi and inquired of Bishop Bigler

if there was a woman in the ward that would likely make him a

good wife. He was recommended to my mother and he made his

acquaintance with her. After a few days they were married

and she moved with him to Parowan, taking her children with

her. Andrew died within a year from that time, leaving my

mother well-provided for, with a farm and a home for her

comfort.

In the spring of 1858 I went to Iron Co. after visiting

with my mother and her two younger children, Thomas and Jane.

I went to work for a man by the name of Thomas P. Smith, who

lived at Fort Johnson (known as Enoch on the map). Their

agricultural resources were so limited that they moved to

Summit Creek in a body. I continued to work for Brother

Smith until the year of 1862 when I went back to Parowan to

take charge of my mother's affairs. When Panguitch was

settled I was one of the pioneers of that place.

In the spring of 1864 I returned to Parowan. One day in

1865 my cousin William Arton told a bunch of young men that

he was taking some supplies to meet some families from

England which were headed for the town of Summit Creek in

Iron Co. I was with Wi11iam and the boys.

We met one family by the name of George and Mary Taylor.

One of the girls in the family really appealed to me very

much. Her name was Ann. This family went to Parowan instead

of Union so I got better acquainted with Ann. She

immediately found work at a farm making butter and cheese and

caring for a family. She soon became a young woman of

marriageable age.

Because of her sweet disposition and outstanding

personality Ann was respected and loved by all who knew her.

She was courted and considered prominent with President

Brigham Young's daughters when they were in Parowan with the

President when he made his visits to all the new colonies.

Ann and I were married on April 23, 1865 by William

Danes, at Parowan Utah, at the home of my mother and

stepfather, Luke Ford, whom my mother had married a few years

after the death of Andrew Bastian. For awhile she helped me

run the farm for my mother, so again she was making butter

and cheese and doing the other duties a housewife did in the

home.

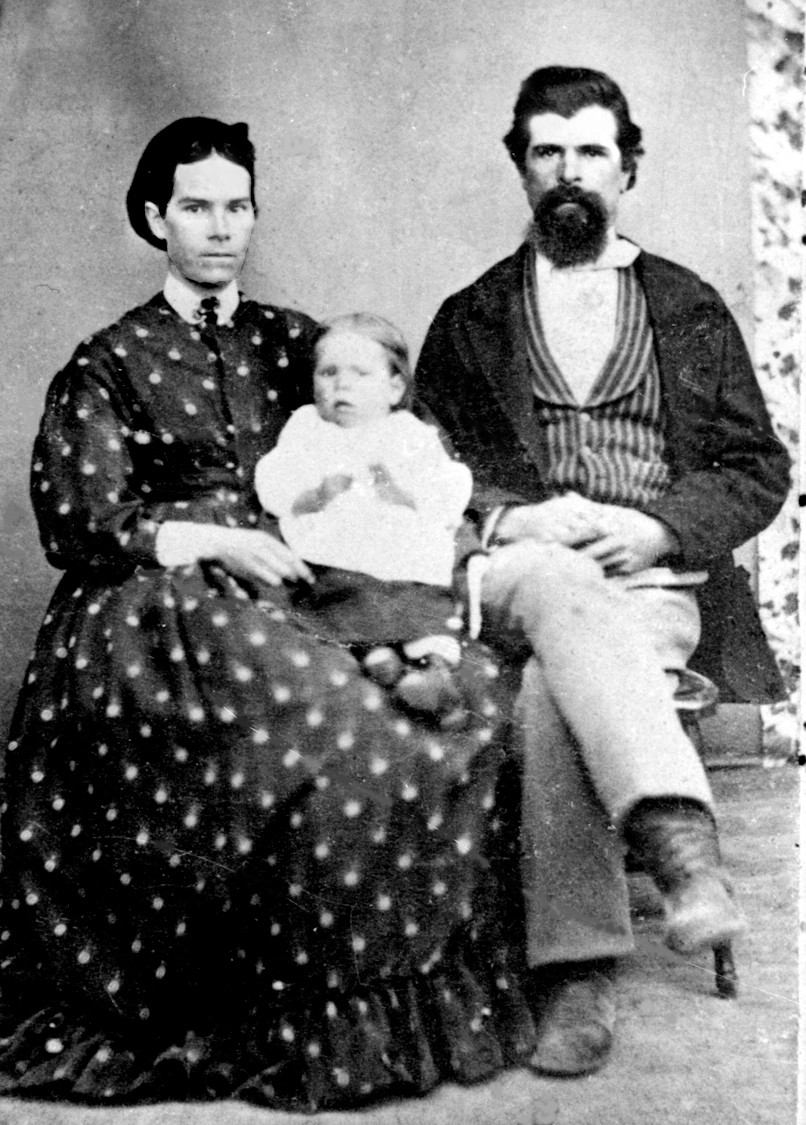

On March 6th 1866 a daughter was born to us. She was

blessed and given the name Mary Ann. Soon after her birth I

took my wife to Salt Lake City to the Endowment House and we

were sealed to each other. We were not able to have our

daughter sealed to us at that time as the sealing of children

to parents had not yet been introduced. That ordinance would

come when the Temple was completed, so we had to wait for

awhi1e.

Our family added a son on the l2th of January, 1868.

He was given the name of Samuel James. He was a husky lad

and grew to manhood and we were proud of him.

By this time we were able to build a three-roomed adobe

house which faced the southeast and which had a porch on the

north and also one on the south. We set out a young orchard

of peaches, apples, plums, and English currants. We also

beautified our yard with shade trees and roses. We were very

comfortable.

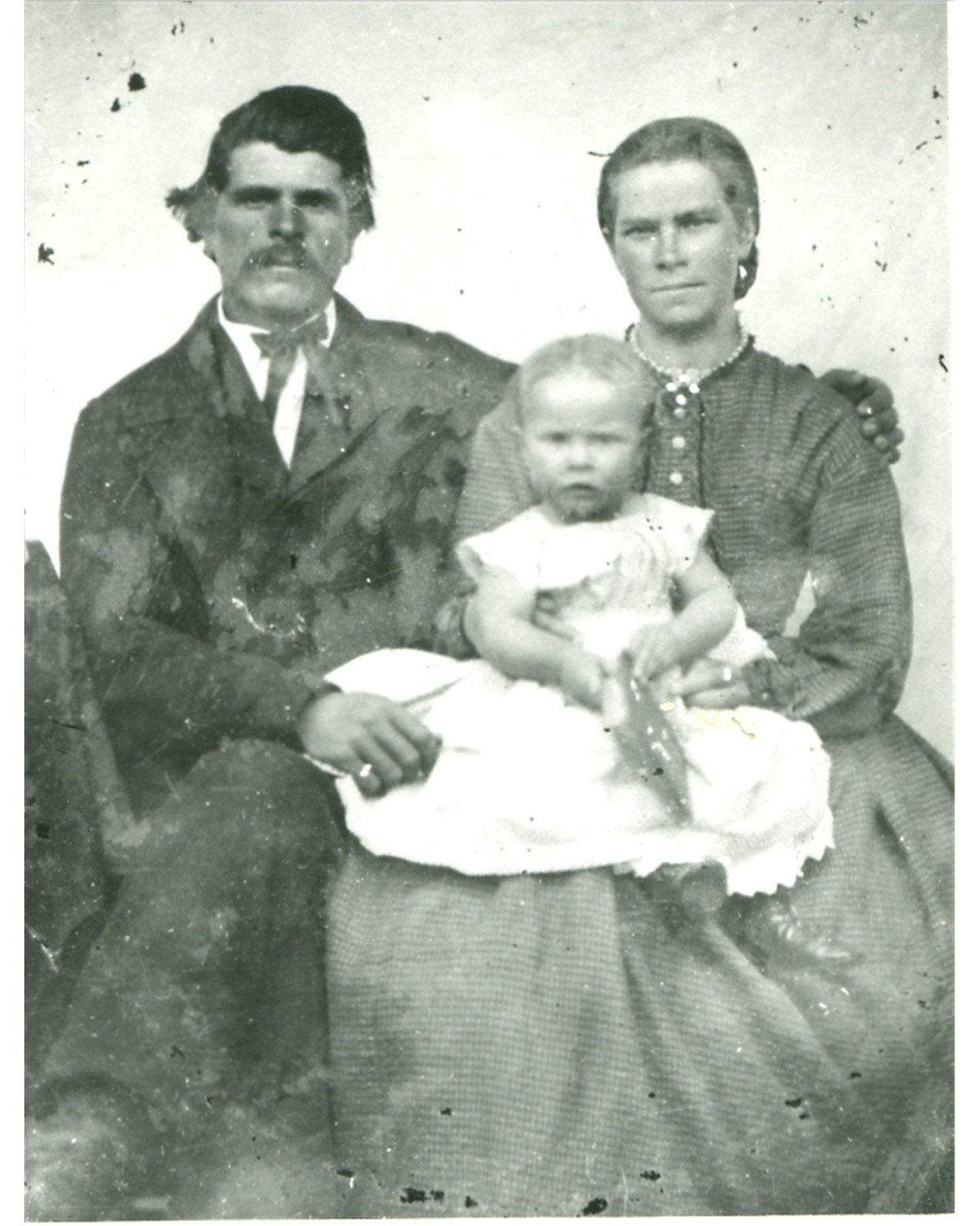

On 20 January 1870 we were again blessed with another

daughter, who was given the name of Hannah Eliza. Hannah was

to honor my wife's sister and my half-sister back in England,

and Eliza was to honor my sister Eliza who died on the plains

and was buried in a snowbank. We still missed her.

Our family was growing as time went on. Another

daughter came to gladden our home on the 15th of July, 1872.

She was given the name of Sarah Jane, Jane to honor my sister

Jane, and Sarah for my wife's sister Sarah. Alice Louisa was

born 11 October, 1874. She was named for my sister.

That same year, President Young came to convert the

Saints to the United Order. I laid all I had upon the altar,

my team, my wagon, my farm, and myself. I worked all summer

and in the fall we found it to be a failure. All that I got

out of it was 14 bushels of potatoes and I had to work for my

bread. Well, that was just a little experience.

A short time after that, my wife's mother died and a

tumor made its appearance on her father's face. My wife was

the youngest daughter. Her father was very lonely so we took

him to our home and cared for him until his death. That was

something we were always glad we did.

Our second son, George Walter, named for my wife's

father, was born 25th of June, 1877, at the home in Parowan,

as were all the others older than him. By this time the

older children were going to school. It seemed they were

growing up quite fast, but they were getting to be able to

help where needed.

At a quarterly conference being held in Parowan in 1879,

I was called on a mission for the Church. I could have my

choice to either go to England, my native land, or to go to

San Juan to help settle the Indians in that area.

At this time I had a family of seven children and had

followed the vocation of farming and had a comfortable home

in Parowan. My wife didn't want to be left alone with the

family to raise, so we decided to go to San Juan so we would

go together and take the children.

Not being able to go in the spring, we were given a year

to get ready. We went in the fall. My mother helped to make

bedding and cookies, and dried fruit to take along. She

helped also, to make a new rag carpet which was put over the

bows on the wagon under the tent, with many pockets sewed on

the carpet to hold the needed everyday things, such as needles

and thread, soap, and combs, etc. The beds, food, boxes of

shoes for everyone, and clothing were put in the wagon.

On the first of September, we were blessed with another

son we named John Taylor. I had always been so close to my

brother John that I wanted the baby to be named for him.

Taylor was my wife's maiden name.

Before we left Parowan to start our mission, I took my

wife and oldest daughter Mary Ann to the St. George Temple to

be sealed to us as they were not sealing children to parents

at the time my wife was sealed to me. Mary Ann also had her

endowments at the same time, as she was thirteen years old

and had become of the right age. We felt that this was

important as we had no idea what we were facing on this

mission to the Indians.

After we got back to Parowan and were completing our

preparations, a meeting was called for our final

instructions, so we would all be able to follow the plans

together. Silas S. Smith was assigned to be General Captain

and Assistant Captain was Platte D. Lyman. At the meeting we

were visited by some prominent men from Escalante telling us

that the best way to travel was not the way we had been

advised by our leaders. These were people we deemed honest.

They had lived in the area for many years. Our leaders,

feeling they should know, took their word for what they said

would be best.

So the Parowan group left our hometown on the 23rd of

October, 1879. Included in our group were my wife and myself

with our seven children, one a seven week old baby boy.

My outfit consisted of two wagons, the first driven by

my wife, Ann, with a fine team of horses we called Prince and

Polly, carrying such things as a small camp stove in one end

and a large box with a till that had sections for knives,

forks, and other utensils, pots, pans, and dishes. We also

had room to sleep in the wagon under the beds.

I drove the supply wagon with a team of three yoke of

oxen. The head team were named Lipp and Pinto, next were

Roan and Redd, and next to the wagon were Broad and Stinker.

This wagon had such things as flour, beans, a large box

of shoes of all sizes, grain, potatoes, etc. My oldest son,

Samuel James, 11 years old, and 9 year-old Hannah, rode

horses and drove the cattle. When they got tired they rode

in the supply wagon.

Going by way of Little Creek Canyon and over the Divide

into Bear Valley, down Bear Canyon to the Sevier River, by

way of Panguitch, Red Canyon and the East Fork of Sevier, up

the Sweetwater Creek and over the mountains into Escalante

Canyon, we found there the part of our company from Beaver.

Our company also waited for the group coming from Cedar City.

The people from Escalante, learning that we were

following their instructions, called a convention and raised

the price of everything they knew we would need to almost

double the price it had been before. They had also told us

at the meeting before we left our home, that the country had

been explored and that the roads were passable. But now we

found out that they had been mistaken or misled.

By the time we reached Escalante there were 83 wagons in

the train. Many of the wagons were in bad condition on

account of the bad roads, and the teams were lame, and the

season was getting late, but the restless colonizers pushed

out, headed for the Forty Mile Spring, where they gathered

early in November, 1879.

By the last of November some seventy families with

eighty-three wagons and hundreds of head of horses and

cattle had congregated at the spring and camped there for

miles around on the desert. We were forty miles from

Escalante and twenty miles from the Colorado River. From

Escalante the roads became worse than before; they were deep

rutted, going over rocky creeks and sinking in deep sands in

the steep, deep washes.

Constant mending of harnesses and wagon repairs were the

order of the drive. Meager equipment was an added burden on

the trek.

Other problems beset the colonizers. The loose stock,

consisting of about 1,800 head of cattle and horses following

along with the wagon train, created a problem. It was hard

to find feed enough for such a large band, making it

necessary to have the service of cowboys to wrangle the

stuff.

One man, Willard Butt, was put in charge of this phase

of the trek, which included driving and ferrying the herd

through the small streams and the Red Colorado and finding

pasture for them. He was a very efficient foreman and with

the help of J.M. Redd, George Decker, and Amasa Barton the

situation was finally under control.

While more settlers were coming in from Escalante to

Forty Mile Spring, other scouting parties, including Platte

D. Lyman, were sent out to see the real lay of the land. One

group of thirteen men was called by President Silas G.

Smith. This group consisted of Andrew Schow, Ruben Collitt,

William Hutchen, Kumen Jones, Cornelius Decker, George Hobbs,

Platt D. Lyman, George D. Lewis, Joseph Burton, Samuel

Bryson, James Rulay, and myself, Samuel Rowley. Our families

remained in camp while we were gone.

Other men and boys that were not called to scout busied

themselves working on roads ahead as well as improving those

they had driven on behind them. The children busied

themselves gathering chips and hooves to boil down for glue

for boats to ferry the entire company across the Colorado

when we got to it.

Our scouting group had two wagons, one loaded with a

boat, the other with supplies. We left on November 28th to

find a way to the Colorado and out on the east side. It took

the party two full days to travel twenty miles northeast to

get to the river. Platte Lyman said it was the worst country

he had ever seen, and we decided as a group that there was no

use of the company undertaking to get through to the San Juan

this way.

When we arrived at the Hole-in-the-Rock, after sixteen

miles of hard driving over rough sandstone hills and sand, we

found ourselves two thousand feet above the riverbed, and we

could find no way to get to the bottom of the cliffs.

Prospecting two miles along up the jagged brow of the

cliff to where it was less abrupt we removed the front wheels

from under the boat and lowered it by hand, zigzagging

downward a mile over and between rugged rocks to a sandy

beach. Across this sand we dragged the load another mile and

slid it two hundred feet over solid surface into the water

about one mile above the hole.

After a late supper we loaded into the boat and tied up

at midnight below the hole. The river here was about 350

feet wide, the current sluggish. and the water milky but of

good taste.

The crossing seemed impossible, the looks of a rugged

terrain most discouraging.

After crossing the Colorado into the San Juan country

and scouting the broken country, the thirteen men returned to

camp.

There were many tries by different groups of men. Seven

men went down the Colorado River to the San Juan, but their

boat ran aground in a rapid and they were forced to turn

back. Then another group of eleven with blankets and few

provisions started up over the bluffs to the east searching

for a way out of the maze.

After several unsuccessful tries to the river through

numerous washes and gullies and over precipitious sandstone

hills, the company on December 1 reached San Juan. Some of

the party were of the opinion that a road could be made if

plenty of money was furnished. Not all agreed, so they made

their return trip to camp. They walked back to the Colorado,

crossed over, and hauled their cart back to the top of the

bank, half a day's hard work, and camped.

On December 3rd, they drove back to camp, much of the

way in the rain. All were wet to the hide. They went back

to the Forty Mile camp. On their return trip, the last group

met a group of men working on a road to Fifty Mile Spring, a

road built over a broken country, leading over numerous

draws. These hardy scouts told the road crew that their trip

had been in vain as they could not get through that way to

their destination (Fort Montezuma). On hearing this the crew

picked up the spades, picks, and shovels and returned with

the scouts to the Forty Mile Spring.

At the regular prayer meeting at the camp, the scouts

gave a report. One of them stated that the solid rock and

rough terrain made it impossible to build any kind of a road.

Most of the others agreed. However, under pressure, George

Hobbs stated his convictions that a road could be built.

Pessimism ran rampant as those unfavorable reports

spread like wildfire. Winter was really upon us. At this

altitude, it was snowing and cold. Cattle were short of

feed, deep snow had fallen in the mountains behind us and a

return trip was almost impossible.

Adverse criticism of going through the "Hole" met with

much disapproval. However, the tireless energy and business

like attitude of President Silas S. Smith made it possible to

adjust to the situation.

At the suggestion of Jens Nielson, a mass meeting was

called at the Forty Mile Spring to discuss the problem. This

meeting was held in the tent of Silas Smith. Some of the

scouts reported favorably with others still contrary. The

company in charge voted to go ahead. Now there were no

dissenting votes.

President Smith weighed the matter prayerfully and

carefully from every standpoint, and concurred with the

company that they should proceed over the proposed route. He

decided to give it a trial.

Platte D. Lyman stated that all expressed themselves

willing to spend three or four months if necessary working on

the road in order to get through.

On December 13, President Smith came from his camp six

miles above the "Hole" and called a meeting at which a

traveling organization was effected with Captain Silas Smith

and Assistant-Captain Platte D. Lyman, in charge in the

absence of Smith.

Captain of 1st l0-Jens Nielson

Captain of 2nd l0-George Sevey

Captain of 3rd l0-Benjamin Perkins

Captain of 4th l0-Henry Holyoak

Captain of 5th l0-Z.B. Decker, Jr.

Captain of 6th l0-Samuel Bryson

Clerk-Charles E. Walton, Sr.

Chaplain-Jens Nielson

On December 14th, President Smith left Fifty Mile

Spring, for the purpose of inducing the Territorial

Legislature to make an appropriation for the road to San

Juan, and to get the Mormon Church to contribute funds. He

obtained $5,000 from the Legislature and $500 from the

Church. This money was used to buy powder, provisions, etc.

These provisions were brought out by several men who came to

assist with the road work. These men had experience with the

use of the powder.

On December 18, 1879, Platte D. Lyman, with a square and

level, determined the grade down the "Hole" for the first

third of the distance to be eight feet to the rod, for the

second third to be five and a half feet to the rod, and the

last part was much better than either of the other two. At

this time there were 47 men working at the Hole and making

good progress, widening the cliff and filling it with sand

and rocks from above.

To make a passable trail down the chasm at first glance

seemed an impossibility. The Hole-in-the-Rock was too narrow

to admit a wagon. The first third of the slope fell eight

feet to the rod, but further down the pitch moderated and

ended in a fairly level landing. This straightened passage,

and several perpendicular ledges below it, constituted the

immediate problem of the company, as did their diminished

provisions and lack of much that was necessary to make a road

to the river. From the top to the bottom of the chasm was

three-fourths of a mile.

On December 17th, another scouting party had been sent

out to go over the proposed route to see if it was possible

to get to Montezuma Creek. Four men were assigned the task.

They took only two pack animals and two riding horses with

them and a small quantity of food and bedding, enough to last

eight days. The maps deceived them, however, and they had

some difficulty finding ways to travel with the horses in

deep snow. It was midwinter and there was no trail to

follow.

George Hobbs and the scouting party related an

experience they had which let them know that the Lord will

provide for his children. Hobbs said it took the first day

to get down to the river by a little trail previously made.

The second day, having crossed the river, they made a little

trail to get out. They then traveled over a bench to what

was called "The Slick Rocks", or "Look-Out Rocks. Just

before they reached these rocks, a herd of mountain sheep,

fourteen in number, came up and followed them for some

distance. The men were quite curious to know what kind of

animals they were, said George.

While the men were cooking breakfast the next morning at

Look-Out Rock, one of these animals came within fifteen feet

of the campfire and stood watching them. Hobbs tried to

catch it with a pack rope, but it was very active in dodging

the lasso. He could have shot it, but he thought it was too

pretty to kill. He followed the sheep for some distance.

They seemed to draw him off down in and through the rocks

until they got to the bottom of the rocks about half a mile

from camp. There the animals left him, so he climbed back

up, following the trail he had just made. He found the other

scouts had been trying to find a way to get down those rocks,

but had returned to camp reporting that they could go no

farther.

Hobbs told them he had already been to the bottom, led

by a herd of mountain sheep. It seemed to be the only

passageway down the slick rocks. They knew the Lord had

answered their prayers and provided the way, showing the Lord

will provide.

These scouts thought they could be back in eight days,

but it was twenty-three days before they returned, tired

after breaking trails in the deep snow.

During the interval while President Smith was in Salt

Lake City making arrangements to secure funds for powder, I

worked with the crew making the road over the remainder of

the way across the desert. I moved on to the Fifty Mile

Spring. From this spring we traveled all the next day in ten

inches of snow. My boots made of valley-tanned leather were

soaking wet and I realized I must take them off before they

froze to my feet. I did this and wrapped my feet the best I

could and continued on the journey.

The next morning we made a fire to cook. Our bread was

so hard that we had to shave it with an ax. We filled a

frying pan with water and put the bread in the pan to render

it palatable.

Before we could approach the Colorado River we came to a

sandstone ledge that stopped the progress of our wagons. On

the other side of the ledge was a little canyon that led to

the river, which was half a mile away.

Shortage of feed made it necessary for part of the

company to camp seven miles back from the river at Fifty

Mile Spring. This was where I made camp with my two wagons

alongside each other. We were as comfortable as we could be

away from home.

Meetings and socials were being held in the tents and on

the rocks. Trails were being blasted down the treacherous

hole. The work was slow down the deep crevice. Six inches

of snow fell as we worked. Now we knew that water was

available in the holes in the rocks. Many of the animals

died or had to be killed due to the lack of food and the cold

weather.

On Christmas Eve. these sturdy men and women danced on

the rocks to the fiddles of Edwin Cox and Charles Walton, Sr.

On Christmas this year the children were anxious to know if

Santa Claus could find them when they were so far from home.

Because of the foresight of their parents and their faith in

Santa, our children hung their stockings on the rag carpet

along with the other useful things, and to their great

surprise and joy Santa too did the impossible. In the

morning, the children found some candy, nuts, mugs, and

mittens that my mother had made before we had left Parowan.

The Decker boys and their wives brought their dinner

over and ate with us in our tent. The dinner was served on

our bed, which was a bedstead with rope cords for springs.

The bedding was removed and a large cloth served as a cover.

The plum pudding was cooked in the boiler, and we also had a

large roast beef, gravy, potatoes, dried beans, and dried

pears. We were surely blessed.

On New Year's Day we rejoiced over the wonderful storm.

The bitterly cold weather did not discourage us, and our

company called on their innate fortitude to endure the

privations they were called upon to bear.

During the first week in January 1880, at Fifty Mile

Springs, Mrs. James (Lena) Decker gave birth to the first

child born in the country (January 3, 1880). My wife Ann was

called upon to be the midwife.

The cliff, which was forty-five feet high, had to be

blasted back. The country above the cliff sloped at about a

45 degree angle. This necessitated blasting about 300 feet

to make a passage large enough to get a wagon through. At

one time fifty men were on the job. Some helped lower men on

ropes over the cliffs and thirty men were working on the road

below, making a dugway through the solid rock in order to get

out on a sandslide. The blasting could only be done by a few

men.

Ben Perkins was called "The Blower and B1aster from

Wales", and he and his brother Hyrum, who also had experience

in the use of blasting powder in coal mines in Wales, were

put in charge of that phase of the work.

The ropes that were used to lower the men over the

cliffs to their work were wearing out. The trail made down

the rocks to the grass-covered ledge for the stock was so

dangerous that many horses slid off and were dashed to the

rocks below, about 1800 feet. This trail was improved and

subsequently used as a pack animal trail for the expedition

to get to the river.

For a time it was necessary to lower the workers to

their labors on ropes. Later a small opening in the cliff

was enlarged and widened into a narrow trail down which men

could crawl on their hands and knees. The supply of powder

was exhausted long before the road was completed.

The major section of the remaining descent could be made

by means of a dugway constructed from materials laboriously

gathered to fill in, but a smooth expanse of slick rock

shelving away at a 50 degree angle was a baffling problem

even for a trained engineer. However, Ben Perkins suggested

that new wide points be forged on the drills and a large row

of holes was then drilled across the solid rock face, with

oak stakes placed in them to hold the debris and brush.

Poles were placed along the rims. These were to keep the

wagons from sliding off.

The brush was gathered from the banks of the Colorado

River, three-fourths of a mile below, in the form of

driftwood and willows. At only a few points could the

workers stand and swing their sledges.

Grooves were made for the upper wagon wheels so that the

wagons would not tip over on the downward trip. This was

done by blasting out the rock and filling in against the

poles. Several horses plunged to their deaths from these

steep unfinished slopes.

On January 22, Arza Judd brought to the camp twenty-five

pounds of giant powder which was sent to the colonists by

President Silas S. Smith from Salt Lake City. (Brother Judd

also brought word that President Smith was sick at Red

Creek.) With this help the work on the road progressed much

faster. The blasted rock fell in this awful chute and helped

make a fill for the road.

On January 26 a start was made to move the wagons down

the hole. Kumen Jones was the first man to begin the

venture. He had a well-broken horse which he hitched to a

wagon belonging to Ben Perkins and drove it down through the

hole. Long ropes were provided and about twenty men and boys

held on to the wagons to make sure that there would be no

accidents because of brakes giving way or horses cutting up

after their long layoff. But all went smooth and safe, and

by the 28th of January most of the wagons were across the

river and work had commenced again on the Cottonwood Canyon

road. Eighty-four wagons came down that road and crossed the

river in perfect safety.

Meeting with slight obstacles on the other side, we

passed up Cottonwood Canyon. The walls at the end of the

canyon were not perpendicular, but sloped back at an angle of

about 45 degrees. We blasted a dugway up the side of this

wall and reached the top in safety. We traveled along for

about 12 miles on a mesa on the north rim of the San Juan

River. Here a baby was born in a wagon.

Getting up to the surface of the earth again, we

traveled on about a day's journey when we had to halt again

for several days. While our work was going on, part of our

members went back to gather stock that we had left on the

Escalante Desert. The road was now built down the sleek rock

and we moved on to the "Lake".

This was a very romantic scene. The Lake was from 5 to

8 rods wide and about 40 rods long. The south end, which was

called the head of the lake, terminated at the base of two

solid sandstone bluffs about a rod and a half apart, back of

which was a beautiful strip of meadow in wonderful contrast

to the mounds of sandstone which contributed largely to the

makeup of this part of the country. In moving along our road

wound around between these knolls of sandstone.

We soon came to a slight divide of this same formation

which was very hard on the animals' feet. We now traveled up

Castle Gulch, some nine miles, where we came to Oak Springs,

which was up on the side of the hill. Here we made another

halt during which we built the road down "Clay Hill". This

work occupied some three weeks.

When the road was finished, we started down. A

snowstorm came and made our progress very slow and miserable.

Our company was composed largely of young married men.

When we came to the top of the hill they would detach their

lead horses and their wives would drive them down the hill

while the men brought the wagons down with one pair of

horses. My wife had driven a pair of horses all the way

while I drove three yoke of oxen, but here I had to drive her

team down the hill. Coming along the road, I passed women

driving their wagons along the road. One woman, Rachel

Perkins, had driven under the shelter of a huge rock and was

holding the team with one hand while carrying her baby in the

other arm.

When we arrived at the bottom again, our oxen were gone,

but darkness was upon us and we had to camp for the night.

We were now at the foot of a hill without wood and with very

little water. It was dark and still snowing. My two yoke of

oxen were gone and I did not know where. My wife made a

sling and gave us each a small portion of food and we went to

bed without any supper.

The next day our scattered company was gathered up and

we moved on a distance that took two days, when we were

confronted by a box canyon walled in with irregular ledges

with an occasional huge rock thrown off. Here we wheeled to

the left, traveled up the side of the gulch until we reached

a crossing, and went back down the other side to within a

stone's throw of where we had camped the night before.

It was the month of March now, with a foot of snow and

the frost coming out of the ground. There was no chance of

dodging a mudhole after a few wagons had passed over the road

and cut in. With much difficulty we traveled on until we

came to Elk Ridge. Elk Ridge was a pine and cedar forest,

and we had to cut our way for about 35 miles through it. We

next found ourselves in the Comb Wash, getting mired in

quicksand. Ourselves and our animals suffered from thirst,

some of the latter becoming unable to pull their loads any

further. It was here that one of my oxen became exhausted

and drank too freely of alkali water and died.

Eventually, we reached the San Juan River at the mouth

of the wash. Here we let the animals rest while we made a

very difficult piece of road. A very steep dugway, a quarter

of a mile in length, took us up to a kind of table land, or

rather, rock, along which we followed with some difficulty.

The company arrived here, adjacent to the present site

of Bluff, on the sixth day of April, 1880. Upon

investigation the following day it was found necessary to

blaze a trail up from the head of a small box canyon which

led up from the northeast corner of our prospective town.

Here we found some tillable land and decided to stay and make

a settlement.

We took the wagon boxes off the wagons and dug a trench

a few feet parallel to the boxes and stuck some cottonwoods

in the trench. We unfastened the wagon cover on one side and

attached it to the cottonwoods to make a temporary room and

shelter. This being accomplished, we set about to ascertain

where our canal would come.

The canal being surveyed, we went to work in earnest to

get the water out. When the canal was finished and we went

to turn the water in, we found that the water level in the

river had gone down and left the head of our canal above the

surface of the water. We tried to raise the water by means

of a dam, but failing in this, we extended the canal up to

where a perpendicular cliff formed the north bank of the

river. Here we tried again to tap the river, with the same

result. By this time it was too late in the season and we

abandoned the work on the canal for this year.

We next built log houses in a square close to each other

for protection from the Indians. Finding it impossible to

raise even a late crop this year, we arranged for the

building of a meetinghouse.

During the summer of 1880 we held our church services

under the shade of a tree that stood on the piece of land

that was alloted to me. It was under the shade of the same

tree that the Bluff Ward was organized with Jens Nielson as

bishop. It was also there that I furnished the bread and in

connection with Joseph A. Lyman officiated at the first

Sacrament service in the San Juan Country.

We managed to finish the meetinghouse by Christmas of

that year. The lumber for the pulpit and the floor we sawed

with a whip saw.

At this place I raised a patch of wheat, cut it with a

hand sickle, threshed it with a stick, and ground it in a

coffee mill. Out of this, bread was made to fill the mouths

of nine people. When the supplies I had brought from Parowan

gave out, I paid $9.00 per hundred for flour from Alamosa,

Colorado.

After two years [perhaps one year] at Bluff it was necessary to work to

get means to feed our families. One of my best horses had

been stolen by the Indians and I had to give $25.00 to get

her back. So, taking the provisions we had, we started back

along the road we had traveled two [the] years before. My

provisions were running short by this time and I had to

return to Iron County to work for supplies.

On this journey we suffered much for water. My dog

perished and a mare belonging to George Ipson fell in the

harness, being overcome with the heat and thirst.

After taking care of our animals, the next thing to

consider was how to cross the Colorado River. When we

reached the river, we did not go to our first crossing, but

went above to a place called Dandy Crossing. When we got

there, we found that the ferry boat was on the other side and

that the owner was in Escalante City.

Our next problem was to get across the river to get the

ferry boat. We took the wagon box sides and cleated them

together and fastened a ten gallon barrel to each end. Then

Zachariah B. Decker, an old Mormon Battalion leader,

volunteered to sit astride this improvised raft. Using a

spade for an oar, he was successful in rowing himself across

to the ferry boat. On the way back, he had to use the oar

with all his strength to keep from going down the stream.

Taking the boat from its moorings, he worked it up the west

bank to where the stream butted against the cliff. All being

ready, he started for the east side of the river. He rowed

for dear life, and it was by the smallest margin that we were

able to catch the rope when it was thrown by the gallant old

soldier. The river butted against a cliff on the east side

immediately below where stood and thus we were able to cross

the stream in safety.

We traveled up Grand Gulch and at noon of the second day

we stopped by a pool of highly-colored water in the wash,

which proved to be so full of minerals that we could not use

it. Lars Christensen and myself mounted a horse and started

in quest of water. We soon found a pool of rain water which

had come down from the cliff some time ago. It was literally

full of polliwogs, but it answered our purpose.

That night, we reached Grand Tank by taking the left

fork of Grand Gulch, traveling between two mountain walls

just far enough apart for a wagon to pass, and somewhat wider

in places. For a distance of about two miles this tank would

remind one of the mouth of a tunnel, or an old-fashioned

brick oven built in the wall and extending into the rock

mountain farther than we could see. Here we laid over for

half a day. We did not see the sun until eleven o'clock in

the morning because of the towering cliffs.

Moving on, we crossed the divide and went down Silver

Falls Canyon. In the mouth of this canyon was a cave to

which on our return to San Juan we drove eight wagons and

camped.

Reaching Escalante Creek, we found it necessary to rest

our animals. Our provisions were almost exhausted. Lars

Christensen and myself started on horseback for Escalante to

obtain supplies. We had not gone more than a quarter of a

mile when we met the ferryman returning to the Colorado

River. Through him the Escalante people sent ample

provisions to last us. I must go back now and state how this

came about.

Edward Dalton, a member of the Mormon Battalion, was a

candidate for the legislature and had visited our company for

the purpose of getting the support of the people in the

coming election. On his return to Iron County, he had passed

us during the early part of our journey, and noticing the

condition of the road, thought that our supplies might run

short. He therefore bought the supplies and sent them by the

ferryman. Now, I could not very well pass over his act of

kindness without mention.

Winding our way over two ranges of mountains that

separated us from our former home, we arrived at Parowan in

due time and found our people all well and glad to see us.

Our people were very kind to us in our homeless condition. I

rented a place that was called a house where my family stayed

the winter of 1882-83 [1881-82] while I freighted from Milford to

Silver Reef and thus we passed the winter. In this so-called

home, my daughter Elizabeth was born on December 27, 1882 [1881].

In the spring of 1883 we returned to the San Juan. When

we came to the mouth of the Silver Falls Canyon we camped in

the aforementioned cave. As we proceeded on our journey,

nothing out of the ordinary transpired and we reached Bluff

in due time.

We took a weiner pig back to Bluff with us in a box

wired to the side of the wagon. Everyone in Bluff gave their

garbage to the pig if they had any. So when it was fat and

butchered, every home in Bluff had a fry.

We also took a few chickens in a box wired to the other

side of the wagon. Now the children had chores to do night

and morning.

We took up our share of the work of building up our town

and developing our resources, which were quite limited.

Stock raising was the only industry from which we could

derive any benefit. Of course, we tried to farm, but our

water supply was so uncertain that we could scarcely do

anything at that. Cane and corn did fine. We planted enough

potatoes and wheat to learn that the climate was not suited

to that kind of a crop.

In the spring of 1884, on account of the abundance of

snow that had fallen in Colorado the preceding winter, the

water of the San Juan were unusually high and my bunch of

cattle had grown pitifully small. I had sold some for

supplies, the Indians had stolen some, and some had strayed

away.

During the summer of 1884, the Indians brought the

measles to our town and our little son, John Taylor Rowley,

died of a relapse. Because the water could not be

controlled, we asked permission from the town council to bury

Johnny on the hill behind us so we could see his grave. So

all other graves were moved there also.

On learning that the head of our canal was in danger of

being washed away, we rallied all our available forces and

proceded to protect our headgate. We found that it was like

pitching straw against the wind. We could accomplish

nothing. Camping back some distance from the river, in the

morning we could see our headgate, partly tangled up in the

trees that had fallen during the night, teetering up and down

to the time beaten by the waves in the stream. I had now

become discouraged.

In my condition, with a large family looking to me for

support, I must go where I could produce something. I talked

the matter over with President Lyman and he said, "Brother

Rowley, go and God bless you!"

Before we left Bluff my sister Louisa had told me in a

letter about the new area in Castle Valley where they had

moved called Huntington, where the prospects were good to

start a permanent home with plenty of water and land.

Through her encouragement we made plans to get to the new

area as early in the spring as possible. She also told us we

could stay with her family until we could get into shelter of

our own. We felt that would be best for us at the time.

So my brother Thomas and Harrison H. Harriman, one of

the seven presidents of the Seventy, and myself made

arrangements to leave at the same time. We traveled together

and when we reached Mancos, Colorado, we were able to support

our families, pay our expenses and have a little left.

We waited at Cheer Butte for the waters of the Grand

River to fall within its banks, which did not occur until

some time in August because of the unusually heavy snowfall

in western Colorado the preceding winter. When we learned

that the waters were receding we prepared to proceed on our

journey to Huntington, Emery County. Reaching the Grand

River about the first or second day of September, we found

that the river was not fordable by any means. We were under

the necessity of unloading our wagons and taking them all

apart. Taking a part of a wagon and a part of a family one

trip and returning for another cargo of the same kind, using

a little rowboat for a ferryboat, we crossed the river in

safety.

On the morrow, we made for Courthouse Rock where we

camped the first night from Grand River. Next day we headed

for Little Grand, which we later learned consisted of a wash,

a section house, and a railroad in close proximity. Here we

found no water except flood water so thick it could hardly

flow. We went on and on. Night came and still we traveled

on until after the moon came up. Now the wagon road crossed

the railroad where we halted by a pool of water in a

excavation made by the grader in building the railroad. On

crossing a little ridge we found we were almost upon the

banks of the Green River. We wanted to cross before the

winds began to blow. However, we could not cross before

evening. The next day the wind blew the hardest I had ever

experienced and it kept up all day.

We reached Huntington Creek near Wilsonville on the

evening of September 9th, 1884, and reached Huntington on the

evening of the 10th. Here I purchased a lot on First North

and East Street.

It was with much difficulty that I secured logs enough

to build a place of shelter for my family. That first winter

I was under the necessity of gleaning logs from any point or

hill or from anywhere adjacent to the canyon road. The road

itself did not reach good timber. Later in the fall I gave a

week's work on the canyon road under the direction of Elias

Cox and J.L. Brasher, the object being more to connect with

Sanpete than to reach timber.

In the mere hut that I was able to build after I reached

Huntington, our daughter Ida was born on February 23, 1885.

Later I made the purchase of a homestead located on what is

now known as Rowley Flat. There, in a log cabin, our son

Thomas Jewell was born on May 2, 1887. The only ones present

were he, his mother, and myself. His brother, Richard Edwin,

was born August 22, 1889 under more auspicious circumstances.

Here I want to relate a remarkable dream. Richard, our

youngest son, was a very affectionate and lovable child, and

on account of him I have wondered if parents could think too

much of a child. Our anxiety for him was great and. his

mother dreamed that she lost her boy--and found him again

after four years. On February 14, 1897, he died. On

February 14, 1901 his mother died, and we believe thus; that

she found her son after four years, and that she was

forewarned of the sadness that would come to our home.

After the death of my dear wife I was not left alone

entirely as I had some unmarried children still at home. But to

comply with the last request of their mother, I made a temporary

home in town for the children so they wouldn't have to walk

through the fields after school and when they were old enough

for night entertainment they would be safe going home.

Those still at home were Elizabeth, who later married

George Collard; Ida, who married Francis Brasher; Jewell,

who married Myrtle Gardner; and Katie Ann, who married

Theodore LeRoy. Katie Ann is Mary Ann Rowley Guymon daughter,

Samuel granddaughter, who he helped raise after Mary Ann died.

One winter when the influenza was invading many homes in

town, my son Jewell and his family became ill with it. My

daughter-in-law Margaret Rowley was a nurse, and she and her

husband by a second marriage were helping in the home.

Doctor Thomas C. Hill was attending those who were ill.

When Jewell became ill, the doctor told Margaret and

myself to send for the family. When we were all there and

saw how low he was we sent to town for the Elders. Before

the Elders arrived, the spirit had left Jewell's body and the

doctor told the nurse to remove the plasters. The sheet was

put over his face and he was pronounced dead. The family all

left the room to console his grieving wife and children.

When the Elders arrived I requested that they administer

to Jewell, having much faith in the power of the Priesthood.

The doctor, not being of the same faith, spoke up and said,

"Do as you like, but it's no use. He is already gone."

The Elders and his brothers and sisters and I went to

Jewell's bedside and I uncovered his face. The Elders

anointed him with the consecrated oil and laid their hands on

his head and sealed the anointing and gave him a blessing.

As the Elders prayed, Jewell coughed. The doctor jumped

up from his chair and went to the bedroom door, and saw

Jewell's eyelids fluttering. Jewell's eyes opened and he

heard the Elders say "Amen." Doctor Hill immediately called

for the plasters to be put on again.

Jewell had gone far enough into the Spirit World that he

saw and recognized his mother who had passed away when he was

fourteen years old. He had a mission to fulfill-he lived to

see his baby boy (who was not even born at the time of his

sickness) fulfill a mission and later be called to be a

Bishop. This was an experience we will never forget. Our

testimonies were greatly strengthened as to the power of the

Priesthood.

After three years of loneliness for my companion, I

married Julia Westover on December 17th, 1903. Our home was

a happy one until December 2nd, 1922. She had suffered with

asthma for many years, and now she had found relief. There

were no children with Julia, but my own children were by my

side and took me into their homes and cared for my needs. I

was never alone after that.

NOTE: At the age of 86 Samuel Rowley was still a

faithful worker in the Church, with unfailing attendance to

his duties in that organization. He loved to attend the

annual Conference in Salt Lake City when he could. He was

crippled with rheumatism to the extent that he had to use a

cane to assist himself in walking.

He had had a serious accident years earlier. Once when

he was freighting an animal frightened his horses. When they

lunged ahead the jolt threw him from the wagon and the hind

wheel ran over his hip. There were no doctors available to

set it in place and rheumatism set in. This caused him to

limp for the rest of his life, but he could travel about by

himself on the train or street car. He was always given a

seat by the pulpit at Church meetings because of his hearing

loss.

On January 1, 1928, he fasted from sun to sun and

walked to church, one and a half blocks from his home. There

he opened the meeting with prayer. He also bore his

testimony as to the truthfulness of the gospel.

On January 4th of that year he was stricken with

bronchial pneumonia which caused his death on January 8th at

the home of his daughter Hannah Eliza Rowley Johnson.

Samuel Rowley was laid to rest in the Huntington

Cemetery, Emery County, Utah, after living the life of an

active pioneer and a true Latter Day Saint. He was the

father of eleven children.

Source:

Autobiography found at FamilySearch portions appear to be

a year later than what actually happened. -- David Walton, Bluff Fort CSM.