Photos

Right-click [Mac Control-click] to open full-size image:

John Rowlandson Robinson

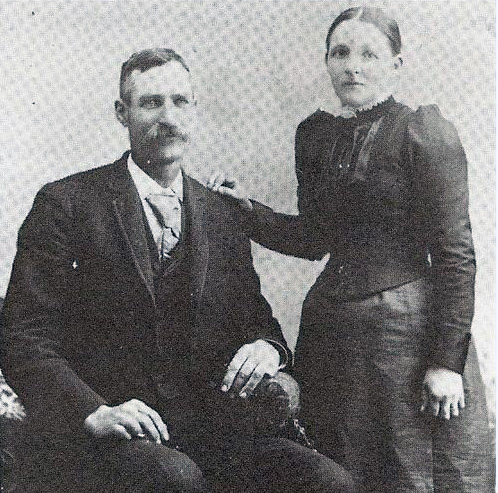

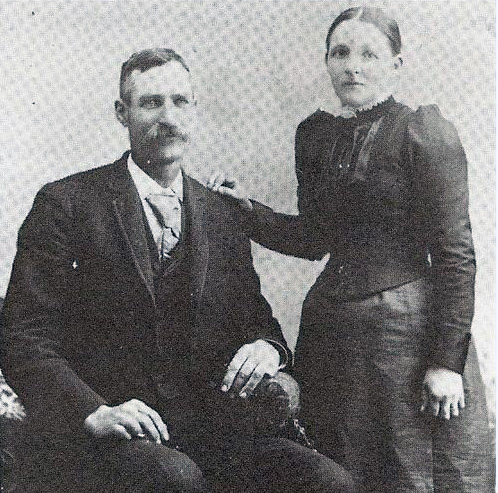

John R. and Emma Schofield Robinson

John Rowlandson Robinson, Jr.

Born: 6 April 1854 at Parowan, Iron, Utah, USAEmma Schofield

Born: 12 October 1853 at Stalybridge,Stalybridge,Cheshire,EnglandLIFE SKETCH JOHN ROWLANDSON ROBINSON, JR.

John was born in Parowan, Utah, on April 6, 1854, to John R. Sr. and Jane Coupe. He was the fifth child in a family of thirteen children and two older children born to his Mother’s sister, Alice. His parents moved to the Fort in Paragonah in 1855 so that was where he grew up.

The little formal education that he had was obtained in the Fort School House during parts of four winters. The school was in session only three months during the winter. At sometime in those early days, John’s Father taught school in his home also. This was primarily for his own children, but he welcomed any child who wanted to join them and desired to learn.

When John was about ten years old, he herded Lowder’s cows with some cattle belonging to his father up over the Dugway. For pay he received enough red striped calico to make a shirt, but his mother did not think it suitable for this purpose, so she used it for something else and made him a shirt out of another piece of material.

During John’s eleventh year, he and two older brothers went with their father to Panguitch with the intention of making their home there. They made the journey in the winter time when the snow was deep and they had a hard time getting through the mountains. Cattle was pulling their wagons and it was necessary to unhitch the cattle, take them ahead to break trail, and then take them back and refasten them to the wagon. In this manner it took them three days to travel three miles.

While at Panguitch, John’s job was to care for the sheep out on the hills to the south and east of town. At this time the Indians were bad and so picket guards were posted. Their duty was to ride to town to warn the people if Indians were sighted. John’s father told him to watch his brother, James, who was a guard and who was easy to keep track of because he rode a white horse. One day John saw his brother start for town, so he ran bare-footed over the rocks and brush as fast as he could. He crossed the Sevier River on a log to get to town. The Indians that had been spotted were not hostile, but were kept in town for a week before being allowed to go on their way.

Continued trouble with the Indians forced the settlement of Panguitch to break up and the Robinson family moved back to Paragonah.

When John was about 14 years old, he was a picket guard out at Little Creek. The guard platform was made on four poles about eighteen feet high and the guard could see all over the valley and watch for Indians. At night the cattle were gathered together and guarded by four of the local men.

John helped some at the saw mill and the grist mill owned by his father, but his main occupations were farming and freighting. At the age of fifteen he took freight to Pioche, Nevada. He made money for his wedding trip to Salt Lake with the freighting.

He met Emma Schofield at a dance and they were married in the Salt Lake Endowment House on October 9, 1873. They were both nineteen. Of course, this trip to Salt Lake was made by wagon. On their return they brought back some of the things necessary to set up housekeeping.

They first lived in a little adobe house probably located at 200 South 100 West in Paragonah. They ranched out at Buckskin. John later traded his interest in the Buckskin Ranch for the home on 200 South Main and they lived there for the rest of their lives.

John started in the sheep business by renting the herd of his brother, James, while he was on a mission. By good management he became very successful, although at one time he sold his wool for only four cents a pound.

On December 28, 1878, at the Parowan Stake Conference, John’s was one of the names called to “settle where directed”. So in late October of 1879 (some accounts say they left in April), leaving his young wife and four small children, he left with a company of one hundred fifty people and about one hundred wagons to settle the San Juan country. This small company began to cut their way toward and through imposing, unexplored territory of snow-capped mountains and towering stone pinnacles. John took fifteen head of cattle with him but they were all lost before they reached their destination.

The winter of their trek was extremely severe. They went by way of Panguitch and through Escalante, building road as they went. One night when it was bitter cold they decided not to cook a hot meal for supper, but instead ate dried apples and drank water. They became very ill during the night and after that they always cooked no matter how cold it was. They found the spring water was so hard that it was difficult to cook their dry beans. John devised another way. When the women, in surprise, asked him how he had been able to cook his beans so quickly, he told them that he had used rain water or melted the snow.

John was one of a group of men who scouted ahead for a place to build the road on their way to San Juan. On one of these trips he found a turtle colored with all the colors of the rainbow. He wanted to take it back to camp to show everyone, but it died on the way and all the colors faded at its death.

At Fifty-Mile Spring one of the few women in the company gave birth to a baby. They both were fine. The company camped at this spring for Christmas Day and held a dance around the campfire that evening.

While seeking the shortest route to the San Juan, these first explorers overcame one obstacle after another but soon faced the largest and most intimidating barrier of all – the impassable gulf of the Colorado River Gorge. Miraculously their weary scouts found a narrow slit in the canyon, a crevice running two thousand feet straight down the red cliffs to the Colorado River below. This lone, near-lethal “Hole in the Rock” seemed to offer the only possible passage to the eastern side.

Many of the group felt it would be impossible to build a road down through the Hole-in-the- Rock, which was a hill of solid rock. Several wanted to turn back, but one said, “This company must go on, whether we can or not.” The majority voted to continue.

For the most part the slice in the sandstone rock they had found was too narrow for horses, or in some places too narrow even for a man or woman to pass through. Sheer drops of as much as seventy-five feet would seem to have made it impossible for a mountain sheep, let alone loaded wagons. But after having traveled this far the hardy Saints were not going to turn back now, so with blasting powder and tools, working most of December and January of 1879-1880, they cut a precarious, primitive road in to the face of the canyon precipice.

In some places a rut was made in the rock deep enough to hold one wagon wheel. In other places, holes were drilled in the rock and pegs were inserted and covered with rocks and brush to make a foundation for the road. Some of the roadbed literally hung on pegs drilled into the canyon wall.

The company camped at Fifty-Mile Spring until the road was finished. And then the task was to get the wagons down the “Hole”. They organized themselves in such a way that twenty men and boys would hold each wagon back with long ropes to slow its descent. The wheels were then brake-locked with chains allowing them to slide but trying to avoid the catastrophe of the wheels actually rolling.

In one of the great moments of pioneer history, one by one the company took the wagons down the treacherous precipice. When, miracle of miracles, they reached the canyon floor they were at the banks of the Colorado River which was the next obstacle in their path. Building a raft they started to ferry the cattle and wagons across. One boy almost lost his life but by the heroic work of the men he was saved.

As they traveled onward, they soon came to a lake where the women and children stayed until they made a road to a place they called “The Cedars”.

After traveling about fifteen miles beyond The Cedars they came to the San Juan River on April 6, 1880, which was John’s twenty-sixth birthday. Here they brought the rest of the company and drew for lots. John never developed the lot he received in the drawing. They worked for two months building a dam across the river to get their water for irrigation.

In June, John and some of the other men went back to the Colorado where they met men with provisions and merchandise sent out by the Church from Salt Lake City. The men paid for the supplies with labor and received credit for the work they had done on the road. John got a pair of boots.

In October 1880, John went home from San Juan to Paragonah after being gone for a year or more. It only took three weeks to make the return journey. He intended to return to the San Juan Valley with his wife and four small children, but his father gave him five acres of land to remain in Paragonah.

He farmed this land and spent much of his time in Bear Valley looking after the Co-op cattle and sheep herds. He was instrumental in getting the Paragonah water system started. He served as water captain for the field company and many other responsible positions. He was a director of the Bank of Iron County from the time it was established until it closed. He was successful in all his business ventures because of hard work and good judgment.

He and his wife, Emma, were the parents of ten children. He had an excellent constitution of body, tall, well set and strong. He was a mechanical genius and was very handy in the use of tools, but his great excellence lay in good understanding and sound judgment. He was a self-educated man through extensive reading, which gave him an exceptionally good store of knowledge. He liked very much to sit and converse with friends and neighbors on current events.

He died February 9, 1939, at his home in Paragonah, after suffering years from a heart ailment. He left eight sons and daughters (two having proceeded him in death), 33 grandchildren and 44 great-grandchildren.

History of my Great-Grandfather would not be complete without writing my memories of him.

Even though I was only seven years old, almost eight, when Grandfather died, I remember well going to his house for Thanksgiving every year. What fun it was to play with all the cousins out on the south lawn and there was a bunch of us. The grown-ups always ate first while the kids played. After they finished eating their leisure meal, the tables were cleared and reset. Probably they even had to wash the dishes because there was always a big crowd. I remember big tables lined up in the dining room and the living room.

Then Grandfather would come out and stand on the south porch and call us to gather around. He would say, “Now children, it is time for you to eat. Come in quietly and take your seats. Those who eat the most potatoes can have the most dessert.” We did walk in quietly and find our place at one of the tables.

A few years ago I had a dream about Grandfather. In my dream, we, as a family, were gathered at the old Robinson home in Paragonah on 200 South Main. Grandfather came out and stood on the south porch, as I remembered him doing all those years ago. I turned to Leland and said, “We must listen to what he says because he is a very wise man.”

This he was – a very wise man! He was certainly looked up to and respected as the

patriarch of his family.

Sources:

1 John Rowlandson Robinson, Jr. (FamilySearch)

Right-click [Mac Control-click] to open full-size image:

John Rowlandson Robinson

John R. and Emma Schofield Robinson