Photos

Right-click [Mac Control-click] to open full-size image:

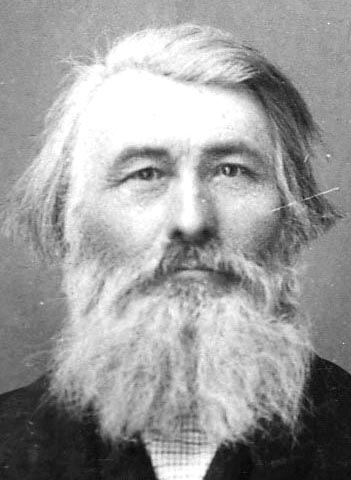

James Harvey Dunton

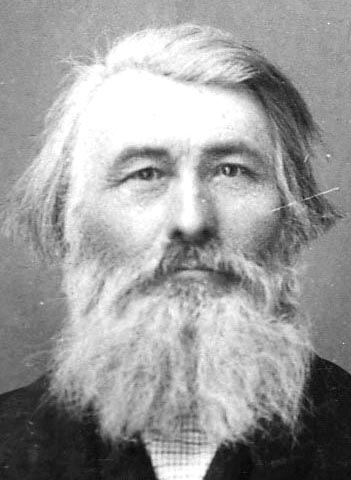

Mary Ann Barker Dunton

James Dunton

Born: 9 Apr 1829 at Howard, Steuben, New York, USA

Parents: James Cyrus Dunton and Mary Comfort Knowles

Married: (2) Mary Ann Doidge Barker, 14 June 1878 at St. George, Washington, Utah, United Stat

Died: 21 MAY 1901 at Paragonah, Iron, Utah, United States

Mary Ann Doidge

Born: 11 April 1837 at Brayshop, Cornwall, England

Parents: John Doidge, Jr. and Mary Nepean

Died: 29 June 1910 at Redmesa, La Plata, Colorado, United States

A brief history of the life of Mary Ann Doidge

Written by her daughter, Madora Barker Burnham

My mother, Mary Ann Doidge, was born in the quaint little town of Brayshop, Cornwall,

England, April 11, 1837. She was the daughter of John Doidge, Jr. and Mary Nepean Doidge.

Her father was a prosperous merchant and provided well for his family. Having hired help

to do the heavy work of the home, Mary grew up in sheltered comfort, learning to cook,

sew and perform the small duties of a household, under the loving guidance of her mother.

She had always lived a carefree life, having only to work as she desired. She was never

an idler, however, but assisted in clerking in her father's store and in preparing

lunches for miners.

She had a fair education for her time, being well versed in Bible scripture as that book

was used as a text for reading. She was also a good writer and speller. She learned to

read the Bible well, and recite the catechisms of the Church of England as her people,

belonging to that church, taught their children that faith.

A child of nature, she loved to roam over the green, rolling hills of the countryside,

gathering wild berries and nuts that were to be found in the woods and flowers that

grew in such abundance everywhere. It was in that country that May Day had its origin

because of the many flowers that bloomed at that time in spring. This day was spent in

dancing, braiding the Maypole and picnicking, by the people who gathered from all the

countryside. More than once she was crowned "Queen of May" in May Day activities.

When my mother was about twenty years of age, she was attending a funeral service of a

relative and while at the cemetery, was attracted by sweet singing coming from another

part of the cemetery where the funeral of a small child was being held. Out of

curiosity and appreciation of the lovely music, she drew close and stood listening to

the beautiful hymn, "O My Father". The words and melody of the song floated to her on

the breeze. As she came nearer, she could hear them singing:

"For a wise and glorious purpose

Thou hast placed me here on earth

And withheld the recollection

Of my former friends and birth.

Yet oft-times a secret something

Whispers, "You're a stranger here,

And I feel that I have wandered

From a more exalted sphere."

Mary Ann had often felt just that way, and had spent much time wondering and meditating

about it. Listening to the sermon which followed, she learned the service was being

conducted by a group of Mormon Missionaries. They observed her interest and asked her if

she would like to visit some of their meetings. Inquiring further she found where she

could attend their meetings. When her people called her to return home with them, she

reluctantly pulled herself away. She accepted the invitation to attend their meetings,

more to hear them sing at first, but later she became interested in their message. She

would often give the Elders money from her own allowance to help carry on their work,

but only secretly, as her parents were very much opposed to the Mormons.

Finally, after much deliberation, she asked to be baptized into The Church of Jesus

Christ of Latter Day Saints. She was very well aware of what it would mean to her but

she knew the message to be the word of God, by the continued gift of the spirit, over

the enlightening principals taught. Things that had been shrouded in darkness for her

were now clear to her mind.

As she expected, her parents outrageously disapproved of this "preposterous act" of

their daughter. Her mother pleaded with tears in her eyes, and her father stormed and

angrily threatened to throw her out of the house if she did not give up this fanaticism.

However, she had the courage to stand by her convictions, and left her lovely home,

with nothing but the clothes she wore. She went to another town where she procured work

to earn her living. This was an added cross as she was not accustomed to hard labor;

never once did she consider giving up the inner joy she had exchanged for the outward

labor. This must have caused her mother deep grief and probably caused her premature

death only four years later. Mary Ann Doidge faced a cold world alone.

She was forced to make her own living for several years.

She was baptized in Devonport, Devonshire, England. It was there she met Joseph Barker,

my father, and they were married at Stone House, Devonshire, England, 11 June, 1860. He

was baptized into the church just a few days previous to their marriage. About a year

later baby Sarah was born to them. Joseph Barker was a tailor but barely made a living,

and they were unable to save money to emigrate to America as they greatly desired.

Finally Mary Ann decided to wean her baby, and putting her on a bottle, she nursed the

baby of some rich people, to earn the money for their transportation.

Her own baby, Sarah, became quite sickly. On the ocean voyage she was very ill and had

spasms. One time they thought her dead, and Mary Ann feared she would have to bury her

baby daughter in the sea, but her life was spared and she reached America. They crossed

the Atlantic in a sailing vessel, taking six weeks to make the trip as they met great

storms that would drive the vessel back for days at a time. During the trip, baby Sarah

threw their one and only comb into the sea. It was while this voyage was being made that

Mary Ann's mother died. Sometime after reaching America, she received a letter from her

father. In harsh, unforgiving words, he wrote, "You have killed your mother; she died of

a broken heart. May the Lord bring judgment on you."

The big problem after reaching America was to find a way to cross the plains and join

those of their faith in Utah. Joseph found a chance to drive a team of oxen; there was

no way for his wife and baby to come at that time, so he went on ahead. Three weeks

later Mary Ann found she could have her baby and few possessions taken, agreeing to do

the laundry for the Captain of the company, and his family. There was no room for her to

ride; she walked all of the 1000 miles from Missouri to Salt Lake Valley.

They were three months on the journey. The days seemed endless with the hot sun burning

into her back and her only shoes worn to shreds. At night she was so tired she could have

slept on a rock as well as on her solitary comforter. Sometimes for weeks there would not

be a tree or a shrub of any kind to break the endless monotony of the dry prairies, and

both the eye and the soul became famished for a haven of rest. At eventide, when they

gathered within the circle of wagons, for song and prayer before retiring, she received

a new strength and courage from an unknown source to carry her through yet another day.

At times when she felt as though she could not take another step, she would softly sing

one of her favorite songs, "Come, come ye Saints, no toil nor labor fear, but with joy

wend your way."

On one especially hard day, everything seemed to go wrong: in the early morning she had

washed for the Captain's family, and herself and baby, by rapidly rubbing the soiled

places between her hands in the water of the stream by which they had camped. When they

came to a stop at noon, she stretched a line between wagons and hurriedly hung the clothes

to dry while the others were eating. No water could be found for the horses so the call

came to move on. Weary and faint, she gathered in the wet clothes and trudged on all

afternoon without the sustenance of food.

In the evening she again hung up the clothes, and then helped prepare the evening meal.

Just as they were ready to eat, the call came to gather for prayers. During the day she

had been more depressed than ever before; she was tired, hungry and discouraged. She had

been shocked to hear the President's son swear at his cattle, she had never had definite

proof that this religion she followed was the truth, nor that there was a future

existence. Had she been wise in giving up her family and friends, her home and way of

life—everything she possessed—for this and the gospel? Such thoughts had gone through

her mind over and over during the day. Could it be she was following a false delusion?

While she was going to join the evening session of prayer, she was completely overcome

by hunger and fatigue; everything seemed to go black and she fell to the ground.

Her spirit seemed to leave her body and she was taken by the hand of a girl companion—who

had died some time before—and led to the Spirit World. There she saw relatives and

friends, all of whom she knew had passed away. Everyone seemed to be engaged in school.

Some of them were learning the rudiments of education they had missed in this life. It

was so very pleasant and peaceful, she longed to stay with them but she knew she must

go back to fulfill her mission upon the earth.

When she opened her eyes, her clothes were wet with water that had been used to try

to revive her. "Oh, Mary Ann", her friends exclaimed, "You gave us such a fright! You

have been unconscious for over an hour—we thought we could never bring you to!" This

experience gave Mother a testimony of a future existence and that progression goes on

after this life. Never again did she waver, but went on to the end of her journey with

steadfast heart.

After reaching Parowan, Utah, they were taken in by some kind people named Moody, until

they could build a place of their own. Theirs was a life of privation and hardship, under

pioneer conditions. Here five more girls were born to them. Dora, the youngest, born June

19, 1873, is the narrator of this story. Both parents worked at anything they could find

to do. Father did hauling to Pioche, Nevada and Mother would do a day's washing on the

washboard, for a quart of molasses or a pan full of flour. In the fall she would take us

to the grain fields, to glean the heads of grain left by the harvesters. This grain was

made into flour for our bread. When the girls would go with Mother to glean, they would

each pick their hands full of wheat, then Mother would call "bundle," and they would all

run with what they had and she would tie it all together. Thus she made play of it. She

had a good sense of humor, made a joke many times.

When Ella was a baby in 1872, they went to Salt Lake City to go through the Endowment

House and receive their sealings. While in the city, they bought their first stove and

a Howe sewing machine. Until this time the cooking had been done over the fire place

and the sewing done by hand.

When Dora was a baby ten months old, Mary Ann was separated from her husband and left

alone to raise her family. She started a school in her home. She was one of the first

teachers in Parowan. In the evenings she had a writing school for adults. As pay she would

take any commodities her pupils could give—wood, food stuffs, leather for shoes, anything

she could use for her family. Finally she had to let the four older girls go into other

homes to work and earn their own living. Sarah, who was fourteen, went to Washington to

work in a weaving factory. Mary, twelve, to Cedar City, to work for Mr. and Mrs. Cory,

Emma to Summit, to a family named Hullett. Before this she had worked in Parowan for

Bishop Dame and his two wives but they said, "We would like the little fat one." This was

Kate, so at eight years of age, "Little Cassie", as we called her, went out to earn her

own way. Later Emma went to Paragonah to work. She even helped with the farm work; her

wages were fifty cents a week and every week the money was sent home to her mother.

Because of the necessity of working out, these older girls were deprived of much of

their education.

Four years after their father, Joseph Barker, left, James Dunton, who already had a wife,

six children and a young adopted Indian girl—asked Mary Ann to marry him; this she did,

thinking she would have help to raise her children. Mr. Dunton was 49 years old at this

time and Mary Ann was 41. A baby boy, John, was the only child of that union. When John

was about a year old, they were called by Brigham Young to go with others to the San

Juan Mission to settle new country and make peace with the Indians. So after all the

hardships as a pioneer in Utah, Mary Ann was required to go to this new place and pioneer

again, with the threat of unfriendly Indians ever hovering over them. Mr. Dunton went

with the first company, to get a claim and build a cabin. When he returned to get his

family, he left all his foodstuff with the people of the fort who were nearing starvation,

saying "I won't need it, I have my gun, and I won't starve."

Early in 1879, Harvey Dunton went with an exploring company by way of Arizona to find a

place for settlement on the San Juan River and build a cabin. The members of that first

group started a settlement which was called Montezuma Fort. After starting a cabin,

Harvey returned to meet up with the main party of "Hole-in-the-Rock" pioneers. He left

all his foodstuffs with the few people who were staying at the fort but were nearing

starvation, saying, "I won’t need it. I have my gun and I won’t starve."

In October 1879, Mary Ann and the three youngest children, Ella, Dora, and John joined

up with the main party of "Hole-in-the-Rock" pioneers, probably traveling with the

families of Harvey’s grown sons from his first marriage who also made the trip: James

Cyrus and Marius Ensign. They traveled in a lumber wagon, bringing what few household

belongings they could, including the stove and sewing machine that she so valued. Previous

to this she had cooked over an open fireplace and spun, woven, and sewed by hand. The

pioneering group headed for the Colorado River not really knowing where they were going

to be able to cross the river. Eventually it was determined that a crossing might be

made where a crevice in the steep cliffs was widened with dynamite, pick and shovel and

much hard work before the wagons could pass through. The descent was so steep, the men

blocked the wheels and then held back on the rear of the wagons to keep them from rushing

into the horses. They finally crossed the Colorado River on January 28, 1880 by driving

the horses and wagons onto a ferry boat. After crossing the river, they still faced

difficult travel over very rugged country before they reached the San Juan, arriving

at their new home in April. The trip that was supposed to take six weeks instead took

six months.

While traveling on this trip, eight-year-old Ella developed a special fondness for her

little half-brother who was less than a year old. Being the oldest child, she was allowed

to ride in the wagon to care for him. She was a motherly type and spent many hours caring

for him and carrying him on her hip even though he was a husky child.

James Harvey Dunton helped his son on the Hole in the Rock route for a distance, then

went back home to get his second wife Mary Ann (1835-1910). Then Harvey and Mary Ann

made the trip through the Hole and to Montezuma with three of their children, two of

which were from Mary Ann's first marriage: Ellen Barker 9, Madora Barker 7, and John

Dunton Jr., 16 months (Ron McDonald).

He with his wife and three youngest children, he left for Montezuma Fort on the San Juan

River. Because of our load on the trip, it was necessary for Mary Ann and Dora to walk much of the way.

Ella rode to take care of the baby, John. This was the second company to go down through

"Hole in the Rock", which was a long narrow crack in the rock walls above the Colorado

River. This crevice had to be widened, with pick and shovel in many places, before the

wagons could pass through. The descent was so steep the men blocked wheels and then held

back on the rear of the wagon to keep it from overturning onto the horses. To this day

one may see the scratches on the rocks made by the hubs of the wheels as they passed

through. The Colorado River was crossed by driving the four horses and the wagon onto a

ferry boat. Little seven-year-old Dora was so afraid she covered her head with quilts.

They spent the winter in a fort on the San Juan River, east of Bluff City, Utah. In

telling the story, Dora says, "I don't know how we lived through that bleak winter. I

remember towards spring, we children gathered leaves from the grease-wood bushes for

greens." The fort was built for protection from the Indians. The houses were touching

each other, in the form of a square, with the fronts facing inside. The children were n

ot allowed outside of the square. During the winter the men made large, frame water

wheels, for the purpose of lifting the water from the river to the irrigating ditches.

This experiment failed, as when the high waters came in the spring from the melting snows

above, the wheels were washed out of the sandy soil and down the river. Thus they lost

all the money and work they had put into the project. So they had to leave San Juan as

did most of the other families. The entire settlement was abandoned later when the river

washed out the fort.

In May, before Dora was eight and Ella ten, they again loaded their belongings into the

wagon, and started for an unknown destination. They moved to a sawmill north of Durango,

Colorado, where Brother Dunton obtained work at a saw mill, hauling wood to Durango and

Mary Ann had washings to do. In the fall, a year and a half later, they moved to Mancos

and took up a farm, living in a tent until Brother Dunton could build a dug-out home for

them. They lived in this hut a year or so until we built a log house on the farm we had

homesteaded. We lived in only one room at first and added another later.

At our new location everyone worked. Brother Dunton grubbed the brush to clear the land

with a common grub hoe, and we girls piled it in big piles for burning in the evening.

The colorful flames leaping into the dusk which had fallen over the valley were a source

of enjoyment for all family members as they ran from one pile of brush to another

igniting the dry wood. That was one of our few sources of recreation in those days.

When the grain matured, Brother Dunton would cut it with a cradle, an implement

consisting of a long knife and several wooden fingers. The fallen grain would be

tossed into a clump by the cradle fingers and my sister, Ella, and I would bind it by

making a band of the greener stems to wrap the sheaf, the ends of which were twisted to

tie the bundle.

Mary Ann planted a garden including fruit bushes as well as vegetables. It was said of

my mother that she never stayed in one place overnight but that she planted some flower

seeds. She soon had a lovely flower garden in our front yard. She also took in washings

from town folk to help support the family. The clothes had to be brought out to the farm

on an old yellow mare, which would often mire down in the swamps which dotted the road

between our home and the community. She never complained and was always glad to get the

work.

From the home the children walked to school in town part of the time and rode a horse

when the roads were bad. The family had a cow and chickens to help provide the living,

and with the extra money Mary Ann brought in, they fared pretty well.

We stayed on that farm until part of the land became swampy, then Brother Dunton went

back to Utah, and we moved to the Park, eight miles above Mancos in the mountains

northeast of there, where Sarah's husband had taken up a farm. Will was always a good

friend to Mary Ann, and offered her part of his land so they built a lumber frame house

and lived there for the summer where they raised some crops and rented cows. In later

years we had a winter home in Weber. In the Park we raised some crops, but mostly Mary

Ann made cheese—she made good cheese and had a ready market for all she could produce,

selling it at 15 cents a pound, which kept up expenses. Every tenth cheese went to the

bishop for tithing.

About two years after the Dunton's left Parowan, the four older girls came to Colorado.

It was just before Christmas, and late in the evening when they arrived. Through the tiny

windows of the dug-out they could see their mother sitting in a chair sewing. Cassie,

unable to restrain her pent up longing, cried out, "I see my mother, where's the door?" T

he girls had to sleep in a wagon box as there was no room in the house for them.

They soon obtained work to make their own way, and help their mother some too, until

they married. Emma was first to wed, in 1884. Her first child, Pearl, was Mary Ann's

first grandchild. Kate was only 16 years old when she got married and she lived in a

one-room log house near her mother. She married in June 1885; Sarah, December 1885; Ella,

June 1888; Mary, during the winter of 1889; and Dora, May 1897. Our half-brother, John

Dunton, stayed with his mother for the rest of her life, and never married, which is sad

for him as he was left alone and went from place to place like a lost sheep.

Mary Ann lived in this vicinity until her death, June 29th, 1910. She had taken seriously

ill in the winter of 1909. She remained faithful to the Church, paid her tithing and was

staunch to the end. She was at the home of Sarah and Will Devenport, at Redmesa, Colorado

when her summons came. She was ill for many long months. Kate came from Montezuma Valley

and stayed to help care for her and Emma was with her much of the time. Both of them were

most faithful attendants. They took turns going there and taking care of her, month after

month, while neighbors sat up during nights for her five months of illness from dropsy.

Dora's son Alma, was born about that time so she could only take night turns at the vigil.

Sometime before her death, she said, "I'll fight it till the last. "What will you fight,

Mother," her daughter asked. "This old death," was her grim reply. She was ever a fighter,

in a sense of the word for what she knew was right. Had she not been, she would have

returned to her home in England, when her brothers wrote her after she was left alone

with her small children. “Just give up that church and come home; we will send you money

and care for you and your children the rest of your lives.” Had she not been of the

toughest fiber, she would not have followed the road that proved to have the greatest

resistance.

Always a love for the fine and beautiful things remained in her nature. It was once said

of her, she never stayed overnight in a place, that she did not plant some flower seeds

in the ground.

May it be that we, who follow in the civilization which was wrought at the hands of such

true pioneers as Mary Ann Barker, when our summons comes, be there to say, "I see my

Mother, where's the door?"

At the time of this writing, 1952, there are only three of us alive. Kate is 83, John is

73 and I am 79. Of her 48 grandchildren, 38 are living and she has innumerable great and

great-great grandchildren who have filled the far corners of the earth.

Sometime (no date) Mr. Dunton had gone back to Paragonah, Utah to spend time with his

first wife, Martha Jane McKee, and family. He deeded his property in San Juan to his

wife Mary Anne and son. Mary Ann asked him to come back and he stayed three years and

two months. He started missing his first family and went back, never returning. I believe

this was mutually agreed upon. Mary Ann spent her last years living near her oldest

daughter and son-in-law, Sarah and Will Devenport. In her last days she said she still

loved Joseph Barker and wanted to be with him in the next life, if possible.

This information about Mr. Dunton was found in a short Biography of James Harvey Dunton

“Pioneer”, received from the Daughters of Utah Pioneers and from our own family

histories.

LaVerne B. Merrill

Right-click [Mac Control-click] to open full-size image:

James Harvey Dunton

Mary Ann Barker Dunton